In pharmaceutical supply chains, compliance failures are hardly spontaneous. They are nearly always in advance of a progressive operational invisibility, a phase during which the systems are still operational, reports are still being broadcast, but trust in the underlying information is being corroded away.

The visibility is an inherent product of the right systems that is assumed to be achieved by most organizations. ERP systems, quality systems, warehouse software, and serialization software are likely to give a true image of material flow and batches and inventory risk. This ought to be adequate in principle.

Practically, informal processes, manual reconciliations and parallel reporting structures develop with time. These accommodations keep the everyday processes going, yet they also enable the operation reality to lose touch with what formal systems are.

At the time that discrepancies become apparent to the leadership, auditors or regulators, alignment has frequently been weakening over months or years. It is also important to know how this erosion is taking place and why it cannot be solved by technology alone so that compliance and operational resilience can be maintained.

Visibility Erodes Long Before Compliance Fails

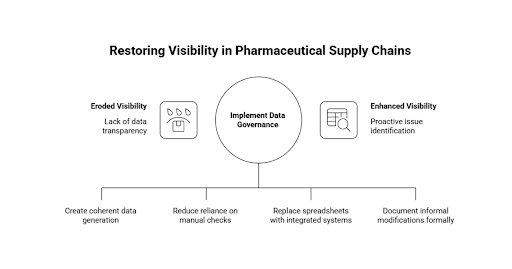

The lack of visibility within pharmaceutical supply chains seldom comes as a consequence of a failure. It evolves slowly, in minor and perhaps sensible changes brought about by operation pressure.

Delay in production, fluctuation of suppliers, quality investigations, workforce rearrangements and changing regulatory factors all bring friction to the day to day activities. Teams make up when systems fail to adapt to these realities as fast as they need to. Ad hoc measures turn into long-term ones. Automated control is compensated with manual checks. Perceived reporting gaps are filled with local spreadsheets.

Initially, these modifications seem to be innocent. They serve to ensure continuity. Shipments move. Batches are released. Customers are supplied. Performance indicators are kept under acceptable levels.

These paralleled practices, however, with time start to redefine the information flow. No longer is there a one and coherent data generation and validation process. Rather, it is compiled using a mix of system outputs, human interpretation and informal reconciliation.

As this happens, visibility is becoming more of a people issue than a people infrastructure issue. Some managers or analysts come up with their own ways of creating sense in the numbers. Specific people are used by decision-makers to elucidate discrepancies. System transparency is substituted with institutional knowledge.

This shift is hardly ever recorded. It occurs informally without being approved and supervised. Governance wise, the organization does not seem to be in revolt. Operationally, however, control is getting weak.

There is no significant danger that compliance will all at once fail, but rather, the leadership will become unable to notice emerging issues sooner. In the case where visibility relies on the interpretation by hand, alerts are slow, distorted or distorted by subjectivity.By the time the structural issues are indicated formally, the response options are frequently constrained.

This is the reason why compliance failure is almost always preceded by visibility erosion. The disintegration takes place initially on the operational level and way before it is manifested by the regulatory or auditing systems.

When Systems Exist, but Reality Runs Elsewhere

The majority of pharmaceutical organizations have very organized system environments. ERP systems control materials and monetary flow. Deviations and approvals are recorded in quality management systems documents. Physical movement is regulated by warehouse systems. Traceability and regulatory reporting are played with the help of serialization tools. Theoretically, these systems constitute a unified control system.

As a matter of fact though operational work will hardly be restricted in practice to formal platforms. Communication occurs via discussions, common folders, e-mails and spreadsheets that are locally managed. Parallel schedules are kept by production planners. Investigations made by quality teams are not part of the formal workflow. Supply coordinators make inventory reconciliation by hand and then make a promise to shipments.

These parallel structures are not created due to the fact that teams do not follow governance. They arise due to the fact that systems can not frequently meet the pace, complexity and variability of the real operations. Exception handling is slow. The specifications of data entry are strict. The reporting takes longer than the time taken to decide. Being pressed to retain continuity, employees devise other ways.

These informal channels are institutionalized over time. New staff members are trained on how things really go and not necessarily how processes are written down. People have internalized critical knowledge but not systems. The process of decision making relies on individual experience and judgment as opposed to the standardised data flows.

Firms may continue to look system-driven on the surface of the system as this trend triggers maturation. Reports are generated. Controls are documented. Audit trails exist. Within the company, however, the most valuable business learnings are increasingly coming out of the non-official platforms.

The lack of connection between them forms a structural blind spot. Leadership is operating on the assumption that it is working with integrated systems when frontline teams are operating with fragmented operation reality. In case problems are detected, the investigations concentrate on single data errors or process failure, but not on the parallel infrastructure that has been becoming a central part of daily operation. As long as this divergence remains unnoticed and unresolved, it is not reasonable to expect that investments in more tools or automation can be used to bring meaningful control back.

How Parallel Workflows Become the Real Supply Chain

As informal processes take root, they gradually evolve from temporary accommodations into the primary mechanisms through which work is executed. What begins as a short-term adjustment becomes an embedded feature of daily operations.

In pharmaceutical supply chains, this transformation often occurs around high-pressure activities such as batch release, deviation resolution, inventory allocation, and shipment authorization. When formal systems cannot support timely coordination across quality, production, and distribution functions, teams construct parallel workflows to bridge the gaps.

These processes are not very often documented in official process documentation. They work with the help of common trackers, email approvals, manual reconciliations, and personal networks. A quality manager has a different release log. A planner of supply is dependent on an individual forecast model. A warehouse manager monitors shortages on his own. The practices have a practical aim in their local frameworks.

With time these parallel mechanisms get more reliable than the systems they complement. Employees understand which reports are not completed, transactions are not timely, and which areas cannot be relied on. They adapt accordingly. Informal approvals are becoming the basis of decisions, as opposed to system outputs.

With the increased use of such structures, formal platforms cease to be operational tools and become places where records are kept. The actions are taken before making entries. The documentation is done retroactively. Systems are indicative of what occurred, and not what ought to occur.

This reversal overturns the nature of control. Behavior does not have systems influencing it but shapes them. Governance becomes responsive. Visibility relies on reconstruction as opposed to real-time insight. At this level, organizations might still achieve regulatory standards, but these are now achieved by people and not systemic integrity. Order is achieved by being on the alert, not by design. The supply chain remains in operation, and its strength is becoming increasingly reliant on personal abilities and institutional memory. Such dependence is fragile in nature. In situations where important staff turnover, when the volume rises, or where the regulatory demands change, parallel workflows which previously allowed flexibility become a basis of instability.

The Point at Which Data Stops Being Trusted

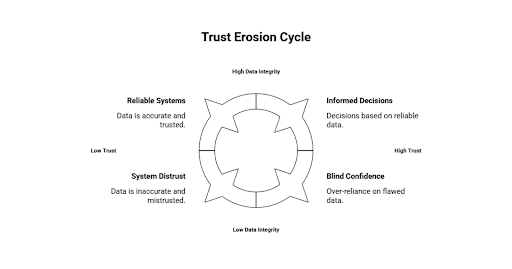

Daily operations of parallel workflows start undermining trust in formal data systems. These changes do not happen overnight. It is built up, as inconsistencies build and informal validations are made the normal.

In the beginning, contradictions seem to be minor. Adjustment of inventory balances is needed. Yields of production are not as high as desired. The quality status reports are in lag of the operational reality. Projections have to be updated regularly. All the issues are fixed by manual measures, which further supports the notion that the systems are helpful but not complete.

These adjustments, however, get normalized with time. Reporting is looked at with suspicion. Dashboards are approached as seeds of knowledge as opposed to authoritative sources. Managers want additional clarifications before taking any action. Meetings have become more concerned with counting the numbers than making sense out of the trends.

The more human interpretation is involved, the less the data will be governed. There is a variation in definitions in departments. Measures are recalculated on-site. Historical comparisons lose their reliability. Although it might seem to be a single reporting environment, in reality, it is a bunch of tailored views and assumptions.

This loss of trust has a direct operation outcome. The process of decision-making becomes slow because of the need of the stakeholders to be assured by more than one source. Risk estimates turn to the right. Opportunities are postponed as there is uncertainty. Whenever issues arise, it would take a long time to find out their origin.

This loss of confidence is especially perilous in regulated environments. Adherence does not just rely on documentation, but it also relies on the legitimacy of information that is embodied in documentation. External assurance becomes even harder to maintain when the internal stakeholders have lost trust in the output of the system.

Organizations at this level usually make efforts to find technical solutions. New layers of reporting are brought in. The deployment of new analytics tools takes place. The data warehouses are increased. Although these measures can help in improving presentation, they seldom succeed in dealing with the underlying disintegration of information flows. Confidence cannot be reclaimed by technology only until data is created, tested, and ingested as part of the coordinated operations.

Operational Drift in a Regulated Environment

In industries which are very regulated, operations are supposed to develop in a controlled and documented way. Alterations to processes, models, and roles are controlled by official methods, certification policies and quality management. Theoretically, this framework should ensure that deviation which is not in line with approved practices is kept in check.

As a matter of fact, operational change is scarcely linear. Continuous variation is brought by market forces, capacity constraints, staffing changes, supplier disruptions and regulatory changes. Teams will evolve gradually to sustain performance, frequently at a rate beyond the capability of formal governance mechanisms to handle.

Therefore, the approved procedures start trailing the actual practice. Documentation captures the manner the work was supposed to be done and not the manner in which it is being done. The validation artifacts are fixed as the operational realities change. The training contents are obsolete. Checking points become obsolete.

This is an imbalance that does not always occur by design. It comes into existence due to a sequence of practical choices that are time pressed. A transient bypass is the order of the day. A standard practice is established as an exception. A system control is replaced with a manual verification. Individually every change seems reasonable.

These deviations build up over time resulting in structural drift. The organization still works in the framework of formal compliance, which is not a reflection of actual workflows anymore. Quality management gets narrowed down to documentation, as opposed to process integrity.

This state of being results in an illusion of safety. Audits may still be passed. There are still chances of inspections producing satisfactory results. The adherence however comes through corrective effort and less through systemic alignment. This latent weakness is revealed when the regulatory expectations become altered, when the volumes grow or when the external scrutiny intensifies. The remediation work is complicated and obtrusive due to the fact that there is no distinct foundation upon which to build.

Compliance sustainability mandates continual alignment of the operational practice with the governing structures. This alignment can never be anticipated to remain stable unless fixed systems are established to measure and reset in case of drift.

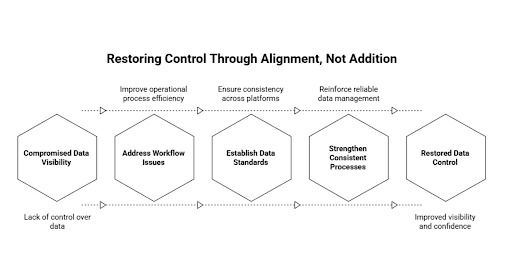

Why Adding More Systems Rarely Restores Control

In the event that visibility and confidence of data are compromised, some organizations usually react by spending more on the technology. Analytics platforms are introduced. Layers on reporting are increased. The introduction of the workflow tools is made. Projects of integration are launched. All these initiatives are aimed at sealing the perceived loopholes and reinstating managerial control.

Such attempts are usually well-motivated. They represent a very real need to consolidate power and modernize infrastructure. They are in most instances backed by good vendor guarantee and industry standards. Technology has come to provide a straightforward and scalable solution.

Nonetheless, new systems are prone to hold on to old issues, instead of destroying them, when the latent operational misalignment is yet to be addressed. Information discrepancies are transmitted across platforms. New interfaces are re-recreated with informal workarounds. Parallel reporting structures are recreated on superior tools.

The burden of coordination increases as well with the complexity of the system. Interfaces have to be maintained. The process of reconciliation multiplies. Exception handling is made fragmented. Users have to move between several environments in order to accomplish everyday tasks. Rather than making operations easier, the technology environment gets obscure.

Accountability is also diffused by this build-up of tools. Whenever problems occur, systems, vendors, and departments are blamed. Managerial causes become hard to separate. Remedial activity is concerned with technical corrective measures but not structural correction.

This is further risky in the regulated settings. Validation efforts expand. Documentation increases several folds. The processes of change management are increased. The company is putting more resources in order to maintain compliance in a convoluted architecture that is becoming even more convoluted.

Technology is best employed in strengthening consistent processes and mutual data standards. It is another complexity when it is deployed as an isolated entity. The restoration of control is not based on accumulation but alignment. Unless the issue of work flow is also addressed the introduction of additional systems only hastens the generation of unreliable information.

The Hidden Business Risk of Fragmented Oversight

As systems multiply and parallel processes persist, oversight becomes increasingly fragmented. Responsibility for data integrity, process compliance, and operational performance is distributed across departments, tools, and informal networks. No single function retains a complete view of how decisions are formed or executed.

In this environment, management relies on layered assurances. Reports are reviewed by multiple teams. Exceptions are escalated through established channels. Approvals are documented. Each layer provides partial validation, but none guarantees end-to-end coherence. Confidence is derived from process rather than from insight.

This fragmentation obscures emerging risks. Inventory imbalances may be visible within planning systems but disconnected from quality release timelines. Capacity constraints may be known to production teams but absent from commercial forecasts. Deviation trends may be tracked locally without influencing strategic decisions.

When information is compartmentalized in this way, early warning signals lose their impact. Issues are addressed within functional silos rather than at the system level. Local optimizations unintentionally create downstream vulnerabilities.

The financial consequences of this structure are often underestimated. Stockouts, write-offs, expedited shipping, production rescheduling, and regulatory remediation consume resources quietly. These costs are rarely aggregated or attributed to governance weaknesses. They are treated as operational noise.

More critically, fragmented oversight weakens organizational accountability. When failures occur, investigations focus on procedural compliance rather than on structural conditions. Responsibility is dispersed. Lessons are localized. Systemic improvement is deferred.

In regulated industries, this dynamic increases exposure. External stakeholders expect demonstrable control over integrated processes, not merely documented compliance within individual functions. When oversight is fragmented, assurance becomes difficult to substantiate.

Sustainable resilience requires integrated governance that connects operational realities with strategic oversight. Without it, organizations remain vulnerable to risks that remain invisible until they become disruptive.

Re-establishing Alignment Before Technology Decisions

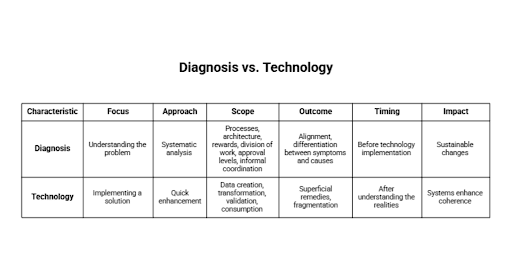

When organizations realize that visibility and control has been compromised the automatic response is to find technological solutions. Advanced analytics, new platforms, and automation tools seem to provide quick enhancement. But without a clear vision of how work does in fact flow nothing is often sustained by such investments.

The restoration of alignment is initiated by the systematic diagnosis. This entails the analysis of the process of data creation, transformation, validation, and consumption in operation and governance processes. It involves the alignment of formal processes with actual processes, where deviations are observed, and the reasons why they continue to happen.

System architecture is not the only thing that can be successfully diagnosed. It entails organizational rewards, division of work, levels of approval and informal coordination processes. Numerous deviations are not based on technical constraints, but structural and behavioral ones that inform everyday decision-making.

In this way, the organizations will be able to differentiate between symptoms and causes. The inconsistencies in reporting can be indicative of upstream data entry pressures. Late releases can be initiated through ambiguous accountability. Disconnected planning cycles could be a cause of inventory volatility. In the absence of this clarity, remedial actions will only be superficial.

Technology can only be implemented responsibly after an understanding of the realities on the ground. Standardized workflow can then be reinforced through integration efforts. Stable processes can be attacked through automation. Trustworthy inputs can be used to base analytical models. AI systems can be controlled by the prescribed framework of decisions.

This sequencing is critical. In the case of alignment being followed by automation, systems enhance coherence. Automation is a faster fragmenting process when it comes before alignment. Organizations with established disciplines in diagnosis in the form of institutionalization of diagnostic discipline preceding significant technology undertakings have higher chances of gaining sustainable changes in visibility, compliance, and performance.

Visibility as an Engineered Outcome, Not a Compliance Byproduct

Many pharmaceutical organizations treat visibility as a secondary outcome of compliance. If documentation is complete, validations are current, and audits are passed, it is assumed that operational insight will naturally follow. Visibility is viewed as something that emerges from regulatory discipline.

In practice, compliance and visibility are related but not interchangeable. An organization may satisfy formal requirements while lacking timely, integrated understanding of its operations. Records can be complete without being coherent. Controls can exist without enabling meaningful oversight.

Positive visibility is developed intentionally. It is represented as workflows, data structure and governance. The creation of information takes place at point of activity and it is verified by standardized controls and then it is availed into forms that would enable timely decision making. Data integrity is well assigned and enforced.

This involves coordination across functional lines. The quality, manufacturing, supply chain, finance and commercial teams have to work under common description and coordinated workflow. Measures should be based on the reality of operations and not on departmental inclinations. Action but not just documentation should be supported by reporting.

In such a way engineered visibility, systems serve as dynamic management tools as opposed to storage facilities. Breaks are observed at an early stage. Trade-offs are considered in an open manner. The threats are dealt with before they become out of control.

Notably, engineered visibility decreases the need to rely on personal expertise. Although professional judgment is imperative, it is made with the dependable information and not its replacement. The fact that insight is institutionalized, not individual, empowers the organization to stay resilient.

By considering visibility as an objective of design, but not a regulatory by-product, compliance is turned to be a basis of operational excellence, instead of a defensive intervention.

Sustainable Compliance Requires Operational Coherence

The documentation, technology and oversight structures alone cannot ensure sustainable compliance in pharmaceutical supply chains. It is a factor of the coherence of the whole operating environment how the processes, systems, data, and decision-making practices operate in coherence.

In cases where there is alignment of operational workflows, governance mechanisms and information systems, compliance comes as a natural outcome of day to day activity. Routine processes have controls inbuilt in them. Statistics represent actual scenarios. The control is founded on timely and dependable insight as opposed to post facto reconstruction.

Deviations which occur in the coherent environments are handled systematically, but not episodically. Root causes are observed at the functional borders. Corrective measures make the underlying structures stronger rather than addressing the individual incidents. The process of learning gets institutionalized and not localized.

It is also coherent and thereby flexible. New regulatory requirements cause changes in markets, or volumes to rise, and without disrupting control structures aligned organizations can change accordingly. The change comes in through consolidated processes instead of being handled by emergency processes.

In contrast, fragmented environments are very much dependent on personal alertness and informal organization. Such systems can operate in a constant environment, but they can be easily ruined. Latent weaknesses may be revealed in a short period by changes in personnel, operational shocks or discovery of the latent weaknesses by increased scrutiny.

In the case of pharmaceutical organizations, the goal is not to stay on course, but to be structured in such a way that compliance is sustainable. This necessitates continuous monitoring of the performance of the work, circulation of information, and accountability.

The attributes of visibility, reliability and resilience are not accidental. They are the products of premeditated operational design. Companies, which invest in coherence, develop supply chains that can be regulated with the necessary confidence as well as long-term performance.