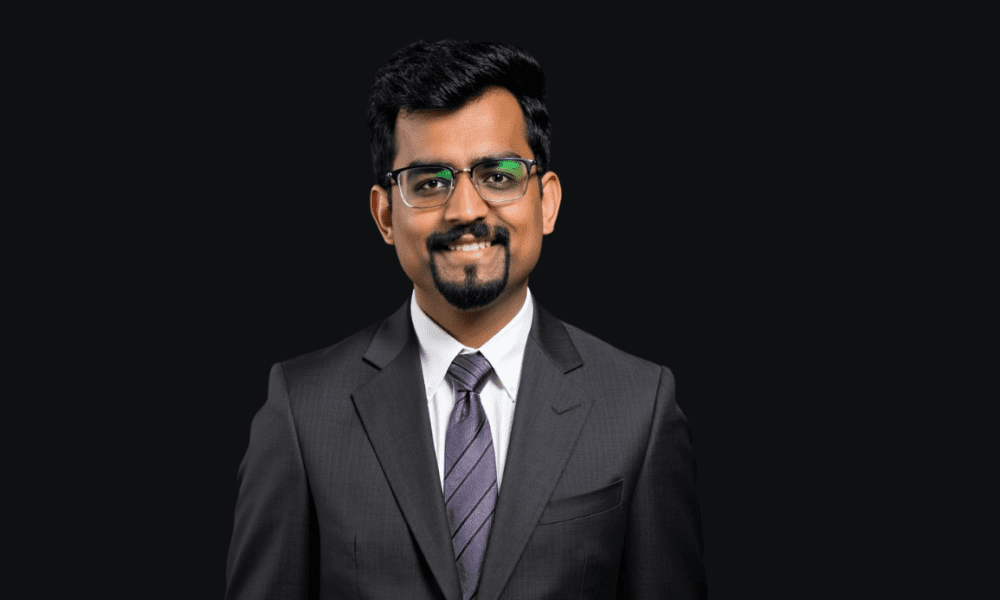

In an era of decentralized energy systems, global decarbonization goals, and growing demand for social accountability in infrastructure development, the question of how to govern large-scale energy programs is becoming increasingly urgent. Amid these challenges, one management analyst is redefining the conversation. Jeffrey Chidera Ogeawuchi, a respected voice in the management sciences, is helping shift the energy sector’s mindset from linear project execution to inclusive, adaptive, and lifecycle-based program management.

His recent paper, “Advances in Stakeholder-Centric Product Lifecycle Management for Complex, Multi-Stakeholder Energy Program Ecosystems,” published in the IRE Journals (Vol. 4, Issue 8, February 2021), introduces a bold framework for how modern energy programs especially those spanning diverse stakeholders and jurisdictions can be governed more intelligently. The ground breaking study represents a strategic shift in how lifecycle processes are designed, evaluated, and managed across the energy value chain.

The timing of this work could not be more critical. Global investments in renewable energy surpassed $500 billion in 2020, and projections from the International Energy Agency (IEA) indicate that over $4.5 trillion annually will be required through 2030 to meet international climate commitments. Yet even with abundant capital, many infrastructure projects—especially in emerging economies—fail not for lack of engineering talent or funding, but because of fragmented oversight, misaligned stakeholder interests, and outdated lifecycle strategies. According to a 2019 World Bank report, approximately 30 percent of energy infrastructure projects in sub-Saharan Africa either stall or underperform due to governance breakdowns and coordination failures.

Ogeawuchi, who is currently affiliated with Brickwall Global Investment Company in Lagos, understands this challenge intimately. His professional work has spanned institutional reform, project analytics, and stakeholder alignment. In this paper, he combines those insights with rigorous systems thinking to build a stakeholder-centric Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) model tailored to the specific needs of energy program ecosystems.

Traditionally, PLM has been associated with industrial manufacturing. It describes the linear journey of a product from design and production through distribution and eventual retirement. But as Ogeawuchi argues, such a model fails to capture the multi-decade, politically sensitive, and environmentally integrated realities of energy infrastructure. “In the energy sector,” the paper notes, “lifecycle stages include not just engineering and procurement, but also resource exploration, environmental permitting, commissioning, decommissioning, and, in some cases, site rehabilitation or repurposing.” These stages are not isolated silos—they are continuous, interdependent, and often influenced by shifting power dynamics among government regulators, financiers, utilities, and local communities.

One of the central themes of the paper is that energy programs cannot be reduced to technical problems alone. They are social contracts—negotiated across time, geography, and institutions. Ogeawuchi’s framework responds to this by proposing a dynamic and inclusive PLM model rooted in stakeholder theory, systems engineering, and ecosystem governance. The model treats each lifecycle phase as a zone of influence—where stakeholders must be mapped, engaged, and integrated in a way that balances technical execution with political legitimacy and social value.

This marks a sharp departure from the metrics that have traditionally defined energy success. Instead of narrowly focusing on financial returns, budget adherence, and technical efficiency, the paper argues for a more holistic approach—one based on shared value creation. These values include environmental outcomes like emissions reduction, social indicators like community health and job creation, and technical co-benefits such as system resilience and grid stability. Ogeawuchi proposes that these dimensions be captured through quantifiable metrics and integrated into decision-making dashboards throughout the lifecycle.

The research further introduces the use of digital twins—real-time virtual models of energy assets that simulate performance, predict failure, and visualize policy trade-offs. In stakeholder-rich environments, these tools allow communities and regulators to preview the impacts of infrastructure projects before they break ground. When paired with AI-driven forecasting and cloud-based dashboards, these digital ecosystems allow project managers and investors to move from reactive to predictive operations.

But Ogeawuchi is also realistic about the institutional barriers to adoption. Many energy organizations operate under siloed, hierarchical structures with limited capacity for cross-functional collaboration. Resistance to change, data fragmentation, and regulatory misalignment are persistent threats to program success. The paper documents how the absence of interoperable systems often prevents even basic information-sharing between project sponsors, government agencies, and local stakeholders—leading to budget overruns, site disputes, and in some cases, total project failure.

To address this, the proposed roadmap includes modular PLM platforms, shared governance mechanisms, and real-time auditing tools such as blockchain registries. These enable energy programs to transition from fragmented legacy systems to integrated digital ecosystems. The idea is not to replace current frameworks but to reorient them around stakeholder input, lifecycle transparency, and strategic foresight.

The implementation strategy outlined in the study is also pragmatic. It begins with a data audit and integration phase, followed by predictive modeling, dashboard deployment, and a continuous feedback loop that updates assumptions and recalibrates priorities in real-time. Ogeawuchi emphasizes that successful adoption hinges on institutional buy-in, regulatory reform, and technical capacity-building—particularly in public sector agencies and community-based organizations.

This stakeholder-centric approach is already being explored in early pilots. According to sources familiar with the research group’s outreach, workshops based on Ogeawuchi’s model have been conducted in Nigeria and Kenya, with interest building in South Africa and parts of Southeast Asia. These workshops involve utilities, municipal leaders, developers, and civil society groups working together to co-design PLM dashboards that reflect both infrastructure performance and stakeholder equity.

Another key insight from the study is that stakeholder roles are not static—they evolve across the lifecycle. For example, government agencies may exert more influence during environmental permitting, while communities become central players during operations and benefit-sharing. Ogeawuchi’s model introduces stakeholder mapping tools that adjust to these shifts and ensure that no actor is marginalized or sidelined. This approach mitigates conflict, improves community buy-in, and reduces the risk of reputational and legal blowback.

The framework also anticipates future developments in energy program design. As microgrids, off-grid renewables, and community-owned energy assets become more prevalent, governance systems must be able to support decentralized, digitally connected, and socially responsive infrastructure. Ogeawuchi argues that stakeholder-centric PLM is especially suited to these trends, as it provides the adaptability, transparency, and participatory structure needed to govern distributed systems effectively.

What’s especially striking about this work is how it balances operational detail with visionary foresight. While some researchers focus narrowly on digital solutions or policy frameworks, Ogeawuchi brings them together—demonstrating how digital infrastructure, stakeholder dynamics, and systems thinking must be woven into a single, coherent management approach. The result is a framework that is both grounded and ambitious, capable of supporting megaprojects and community microgrids alike.

His voice has begun to influence academic curricula, donor strategy sessions, and infrastructure policy roundtables. Increasingly, his work is being cited not just in scholarly circles but also in the operational playbooks of energy planners who are confronting the twin challenges of climate change and energy access. His model speaks directly to the needs of 21st-century infrastructure: it is agile, inclusive, accountable, and future-ready.

Jeffrey Chidera Ogeawuchi is not merely a scholar of management systems—he is a practitioner shaping how energy infrastructure is designed, governed, and evolved. In a world where complexity is the norm and stakeholder resistance can derail billion-dollar projects, his contributions are helping to restore coherence, clarity, and credibility to the infrastructure process. His PLM model is not just a theoretical exercise; it is a timely intervention into a sector that urgently needs new tools, new rules, and new ways of thinking.

At its core, the message of his work is simple but powerful: infrastructure must serve people, not just markets. And the only way to ensure that is to involve those people—meaningfully, consistently, and throughout the lifecycle. In that sense, Ogeawuchi’s stakeholder-centric PLM model is more than a tool. It’s a statement about what energy systems should be and who they should serve.