Late-onset psychosis is a mental health condition marked by the emergence of psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations in individuals typically aged 60 years and older. This condition, which is distinct from early-onset psychosis, presents unique clinical challenges and considerations due to the aging population it affects. Epidemiologically, late-onset psychosis is less common than its early-onset counterpart but carries significant implications for patient care and management, making its study and understanding crucial for effective treatment[1].

Diagnosing late-onset psychosis is complicated by the need to differentiate it from other neurodegenerative disorders, delirium, and substance-induced psychosis. Advanced imaging techniques, such as MRIs, are often employed when neurological symptoms suggest an organic cause, although routine screening is generally not recommended due to its minimal diagnostic yield[2]. Age-specific criteria are also important, with cases arising between ages 40 and 60 classified as late-onset schizophrenia and those occurring after age 60 termed very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis[3].

Current treatment protocols advocate for the integration of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy to manage the complexities of late-onset psychosis. Pharmacotherapy typically involves antipsychotic medications to alleviate symptoms, while psychotherapy provides cognitive and behavioral strategies to improve mental health management. Although the empirical evidence supporting this combined approach is still evolving, integrating these treatments has shown promise in enhancing overall outcomes and reducing symptom recurrence[4][5].

Despite the potential benefits, combining pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in treating late-onset psychosis remains a topic of debate among researchers and clinicians. Some argue that this integration may not always be efficient or effective, given the dominance of the medical model favoring biological explanations and treatments[6]. Nonetheless, ongoing research and case studies highlight the importance of a nuanced, individualized approach to care, emphasizing the need for further studies to refine and optimize treatment strategies for this vulnerable population[7].

Overview

Late-onset psychosis is a condition characterized by the emergence of psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations in individuals typically aged 60 years and older. This condition is distinct from early-onset psychosis and often presents unique clinical challenges and considerations. Epidemiological data indicate that late-onset psychosis is less common than its early-onset counterpart, but it carries significant implications for patient care and management.

The clinical presentation of late-onset psychosis often includes symptoms similar to those seen in schizophrenia, but with some distinctions in the context of aging. The etiology is multifactorial, involving genetic, neurobiological, and environmental factors. Notably, individuals with the APOE-ε4 allele may require more intensive monitoring and additional interventions as they age, although these findings need further replication in clinical studies[1][2].

From a diagnostic perspective, it is crucial to differentiate late-onset psychosis from other neurodegenerative disorders, delirium, substance-induced psychosis, and the effects of prescribed medications and illicit drugs[1]. Advanced imaging techniques, such as MRIs, are often employed when focal neurological findings suggest an organic cause for psychotic symptoms, although routine screening in first-episode psychosis patients is generally not recommended due to minimal diagnostic yield[3].

Current treatment approaches emphasize a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, although the empirical evidence supporting this integration is still evolving. The medical model often favors biological explanations within a diathesis-stress framework, which has led to debates about the validity of diagnoses and the effectiveness of targeted pharmacological treatments[4]. Consequently, there is a need for more elaborate research on comorbid physical conditions and their clinical influence on late-onset psychosis[1][2].

Diagnostic Challenges and Considerations

Diagnosing late-onset psychosis presents several unique challenges compared to diagnosing psychotic disorders in younger populations. Firstly, it is crucial to differentiate between primary psychotic disorders and psychotic symptoms that may be secondary to medical or neurological conditions, medications, or illicit drugs[3]. This differentiation is critical because the etiologies for psychosis in late life differ significantly from those in younger individuals, with a greater incidence of secondary causes such as neurodegenerative disorders and other comorbid medical conditions[1][3].

Although the DSM-5 and ICD classification systems do not provide a formal definition of ‘psychosis,’ they list psychotic features, including delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking (speech), grossly disorganized motor behavior (including catatonia), and negative symptoms[3]. The World Health Organization has also updated the ICD-11 to distinguish more clearly between primary psychotic disorders and other causes by renaming ‘F2 Schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders’ to ‘Schizophrenia spectrum and other primary psychotic disorders’[3].

Late-onset psychosis is often associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates than early-onset psychosis, complicating the diagnostic process[1]. The condition requires careful consideration of differential diagnoses, including neurodegenerative disorders characterized by delirium, substance-induced psychosis, and the effects of prescribed medications[1]. Regular imaging, such as MRIs, may be used in patients with focal neurological findings suggestive of an organic cause for psychotic symptoms, although routine screening is generally not recommended due to minimal diagnostic yield and clinical usefulness[3].

Additionally, clinical studies have proposed various age cutoffs to define late-onset psychosis. A consensus has been reached that cases with onset between ages 40 and 60 should be termed late-onset schizophrenia, while those occurring after age 60 should be classified as very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis[5]. This distinction is crucial for appropriate diagnosis and treatment planning, as different age groups may present with different clinical features and treatment responses[6].

Interplay Between Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

Integrating pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of late-onset psychosis has been a topic of significant clinical interest. Both treatment modalities offer unique benefits, and their interplay can provide a comprehensive approach to managing the complexities of this condition. While pharmacotherapy primarily targets the biological underpinnings of psychosis, psychotherapy addresses cognitive, behavioral, and emotional aspects, often enhancing the overall effectiveness of treatment.

Complementary Roles

Pharmacotherapy typically involves the use of antipsychotic medications to manage symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations. However, evidence suggests that psychotherapy can be an effective standalone treatment for certain patients, especially those who may not require immediate pharmacological intervention[7]. Psychotherapy offers cognitive and behavioral mechanisms that help individuals manage their mental health through lifestyle changes and cognitive strategies, fostering a better understanding of oneself and others.

Combined Treatment Efficacy

Although it is common clinical practice to combine pharmacotherapy with psychotherapy, the effectiveness of this integrative approach has been debated. Some researchers argue that combining these treatments has not shown significant efficacy in practice and may represent an inefficient use of mental health resources[8]. A critical review of several articles indicates flawed empirical evidence supporting the integration of these modalities, suggesting a dominance of the medical model that favors biological explanations and treatments[4].

Practical Considerations

When pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are integrated, the collaboration between two clinicians—one providing medication and the other delivering therapy—adds layers of complexity to treatment[4]. Courses designed for psychiatry residents often review the literature, discuss various treatment models, and outline the skills required for effective collaborative care[4].

Despite the complexities, combined treatment is often warranted in cases of chronic depression, psychosocial issues, intrapsychic conflict, and co-occurring disorders[9]. Poor adherence to pharmacotherapy may also necessitate combined treatment, with psychotherapy focusing on improving treatment adherence and addressing underlying psychosocial factors[9].

Evidence and Outcomes

Research indicates that immediate antipsychotic treatment following the onset of psychosis may be associated with poorer long-term outcomes, highlighting the need for a nuanced approach that includes psychosocial treatments like psychotherapy[7]. For patients with partial responses to single treatment modalities, combined treatments have shown potential in enhancing overall outcomes and reducing the recurrence of depression and other symptoms[9].

Evidence-Based Treatment Protocols and Guidelines

Evidence-based treatment protocols for late-onset psychosis emphasize the importance of integrating both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy to optimize patient outcomes. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for psychosis (CBTp) is widely recommended in international treatment guidelines, although these recommendations are predominantly based on studies conducted in community settings[10]. The approach for inpatient settings remains less well-defined, highlighting the need for systematic reviews to explore the potential size and scope of existing literature and to identify ongoing or planned research[10].

Combining pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is common clinical practice for managing complex cases, including those with late-onset psychosis. While pharmacotherapy, particularly antipsychotic medications, is a cornerstone of treatment, these medications are not curative but effective in reducing and controlling many symptoms[11]. Guidelines suggest starting with the lowest effective dosage to minimize side effects while achieving short-term efficacy[2].

Psychotherapy plays a crucial role in promoting recovery by offering cognitive and behavioral strategies to help individuals manage their mental health. These interventions can include psychoeducation, coping skills training, and providing a dialogical space for patients to navigate changes and understand their diagnosis[7]. However, the literature underscores the importance of flexibility within fidelity, allowing practitioners to tailor their approaches based on individual patient needs rather than rigidly adhering to protocols[12].

Combined treatment may be particularly beneficial for patients who have experienced partial responses to single treatment modalities, those with chronic depression, interpersonal problems, or co-occurring disorders[9]. Despite some debate on the efficiency of combining treatments, evidence supports the integrative approach for conditions such as major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders[8].

For caregivers and families, continuous support alongside patient-oriented interventions is recommended to improve treatment adherence and outcomes[2]. The integration of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy often involves collaboration between multiple clinicians, which adds complexity to the treatment process[4]. Further research, particularly involving larger and more diverse samples, is needed to refine treatment approaches and ensure their effectiveness across different populations and settings[2].

Case Studies

Case Study 1: Paraphrenia in Older Adults

A notable case fitting the concept of “paraphrenia,” a chronic psychotic disorder emerging in old age, demonstrates the practical application of combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. The therapeutic goals for this case included establishing a therapeutic bond, validating the patient’s emotions, titrating antipsychotics according to tolerance and response, coordinating with neurologists for anti-dementia drug prescriptions, and working with social services to provide social support. Furthermore, legal institutions were informed with the patient’s knowledge to consider protective measures. This case highlighted several teaching points, such as the differential diagnosis for “late-onset” psychosis, which includes conditions like delirium, drugs, disease, dementia, depression, and delusional disorder or schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The specific clinical features of late-onset psychosis are often not considered in current international diagnostic criteria, and organic factors may significantly influence its presentation[2][6].

Case Study 2: Integration of Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy

In another case, the integration of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy was explored in a postgraduate course for third-year psychiatry residents. This course reviewed the literature and various treatment models, focusing on the technical skills and issues in collaborative care. However, a critical review of three articles revealed flawed empirical evidence supporting the integration, noting that the dominance of the medical model favors biology within a diathesis-stress framework. Despite the common clinical practice of combining these treatments, some researchers argue it has not been proven effective and may be an inefficient use of limited mental health resources. Nonetheless, the course aimed to equip residents with a comprehensive understanding of the complexities involved in collaborative treatment models [4][8].

Case Study 3: Treatment of Moderate to Severe Major Depressive Disorder

A further case examined the utility of combining psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating moderate to severe major depressive disorder. Indications for combined treatment included chronic forms of depression, psychosocial issues, intrapsychic conflict, interpersonal problems, or co-occurring Axis II disorders. Patients with a history of partial response to single treatment modalities or poor adherence to pharmacotherapy might benefit from an integrated approach. Discussing the use of combined treatment with patients was also emphasized, as this method could improve treatment adherence and overall outcomes[9].

Future Directions

The future of integrating pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of late-onset psychosis hinges on several promising avenues for research and clinical practice improvements. One of the foremost goals is to enhance the efficacy of both therapeutic modalities through structured discussions and collaborative treatment models[4]. Such discussions are crucial in group therapy settings, milieu environments, and with individuals who may be reluctant to openly address interpersonal issues. Vignettes from group sessions illustrate the benefits of integrating medication discussions to advance group processes, thereby highlighting the importance of collaborative treatment approaches[4].

Future research should focus on larger sample sizes and multi-country consortia to develop a more comprehensive understanding of late-onset psychosis[2]. Unified operational definitions for diagnosis and standardized treatment protocols will be instrumental in elaborating the clinical characteristics of this condition. Additionally, there is a need for slow titration of antipsychotics, monitored closely for tolerance and response, to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes[2][6].

Another critical area for future investigation is the coordinated evaluation of anti-dementia drugs in conjunction with neurologists, aiming to tailor treatments more precisely to individual patient needs[6]. Collaborating with social services to devise effective strategies for social support, and involving legal institutions to consider protective measures when necessary, are also key components that warrant further exploration[6].

Furthermore, developing training programs for psychiatric residents and other mental health professionals can enhance the integration of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Such programs should focus on reviewing existing literature, discussing various treatment models, and refining the technical skills required for effective collaborative care[4]. By fostering these interdisciplinary collaborations, we can better address the complex needs of patients with late-onset psychosis and improve their overall treatment outcomes.

Conclusion

Integrating pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of late-onset psychosis offers a comprehensive approach to managing this complex condition. This research highlights the necessity of combining antipsychotic medications with cognitive and behavioral strategies to address both the biological and psychosocial aspects of the disorder. Diagnostic challenges, including differentiating late-onset psychosis from other neurodegenerative disorders and substance-induced psychosis, underscore the importance of a nuanced and individualized treatment plan[1][4].

The findings suggest that this integrated approach can enhance patient outcomes, reduce symptom recurrence, and improve overall mental health management. By leveraging the strengths of both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions, clinicians can provide more effective and holistic care for elderly patients experiencing psychosis. Continued research and refinement of these integrated treatment strategies are essential to optimize care for this vulnerable population, ensuring that advancements in both fields are utilized to their fullest potential[2][3].

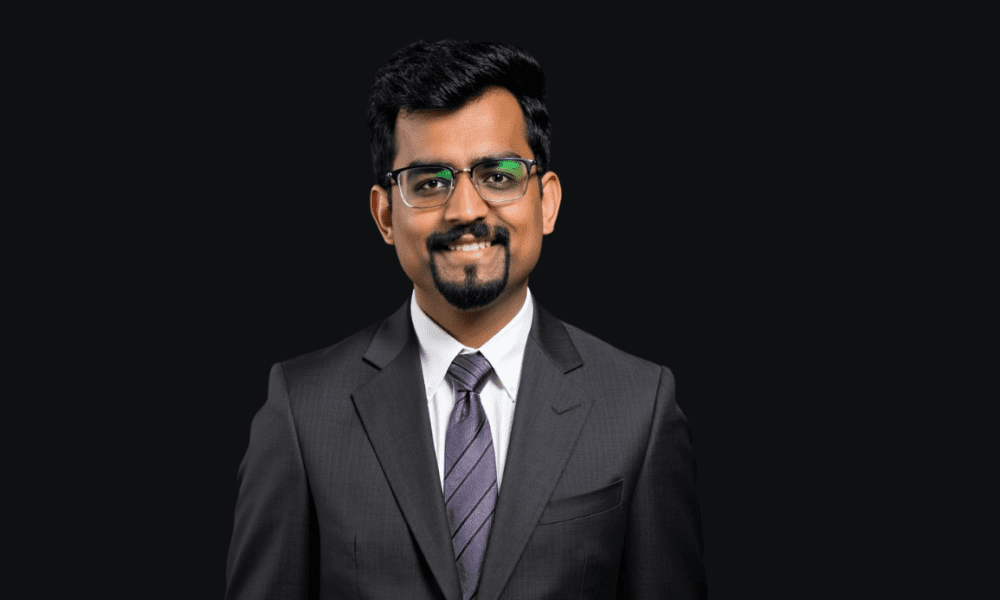

Navneet Iqbal, MD

About The Author

Dr. Navneet Iqbal, MD is a distinguished psychiatrist specializing in Geriatric and Forensic Psychiatry. She completed her Geriatric Psychiatry fellowship at Stanford University School of Medicine, where she honed her expertise in addressing complex mental health issues in older adults. Currently, Dr. Iqbal serves at Napa State Hospital, where she integrates advanced pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy techniques in her practice. Her research focuses on innovative treatment modalities for late-onset psychosis, aiming to improve patient outcomes through a holistic approach. Dr. Iqbal is dedicated to advancing the field of psychiatry through continuous learning and evidence-based practices.

References

[1] García-Baamonde, M. E., Marchena-Giráldez, C., Garcia-Baamonde, J. L., & Benítez-Borrego, S. (2022). Impact of sleep deprivation on academic performance in health sciences students. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(3), Article 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12030381

[2] Kim, K., Jeon, H. J., Myung, W., Suh, S. W., Seong, S. J., Hwang, J. Y., Ryu, J. I., & Park, S.-C. (2022, March). Clinical approaches to late-onset psychosis. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(3), Article 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12030381

[3] Tampi, R. R., Young, J., Hoq, R., Resnick, K., & Tampi, D. J. (2019, October 16). Psychotic disorders in late life: A narrative review. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 9, Article 2045125319882798. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125319882798

[4] Sparks, J., Duncan, B. L., & Miller, S. D. (2008). Integrating psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 17(3), 83-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J085v17n03_05

[5] Howard, R., Rabins, P. V., Seeman, M. V., & Jeste, D. V. (2000). Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: An international consensus. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(2), 172-178. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.172

[6] Gracia-García, P., González-Maiso, Á., & Romance-Aladren, M. (2017). Diagnostic and therapeutical challenges of late-onset psychosis. Journal of Psychology and Cognition, 2(4), 218-220. https://doi.org/10.35841/psychology-cognition.2.4.218-220

[7] Faith, L. A., Hillis-Mascia, J. D., & Wiesepape, C. N. (2024). How does individual psychotherapy promote recovery for persons with psychosis? A systematic review of qualitative studies to understand the patient’s experience. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), Article 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060460

[8] Kuzma, J. M., & Black, D. W. (2004). Integrating pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the management of anxiety disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 6(4), 268-273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-004-0076-y

[9] Busch, F. N. (2020, January 30). Integrating psychotherapy and psychopharmacology in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychiatric Times, 37(1). https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/integrating-psychotherapy-and-psychopharmacology-treatment-major-depressive-disorder

[10] Jacobsen, P., Hodkinson, K., Peters, E., & Chadwick, P. (2018). A systematic scoping review of psychological therapies for psychosis within acute psychiatric inpatient settings. British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(2), 490-497. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.106

[11] Better Health Channel. (n.d.). Antipsychotic medications. State Government of Victoria. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/antipsychotic-medications

[12] Cook, S. C., Schwartz, A. C., & Kaslow, N. J. (2017). Evidence-based psychotherapy: Advantages and challenges. Neurotherapeutics, 14(3), 537-545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-017-0549-4