As nations scramble to meet their climate targets, the question of how we design, retrofit, and operate buildings has taken centre stage. The built environment is responsible for 38% of global energy-related carbon emissions, with heating, cooling, and lighting among the largest contributors. In the UK, buildings alone account for nearly 25% of national emissions. In Nigeria, the lack of grid access for over 85 million people has created a parallel emergency—one where polluting diesel generators power urban life while the poor are left in darkness. The climate crisis, in both places, is playing out through bricks, steel, glass, and most urgently, energy.

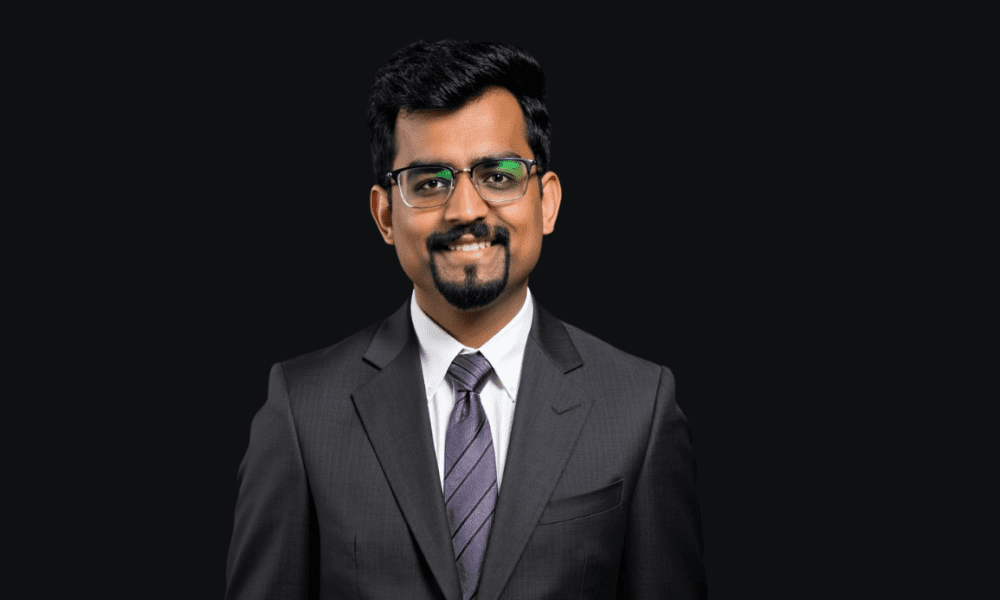

At this pivotal intersection of architecture, climate policy, and renewable energy integration stands Ifechukwu Gil-Ozoudeh, a Nigeria-based expert in sustainable design systems. With a reputation growing steadily across continents, Gil-Ozoudeh is fast becoming one of the most respected voices shaping how buildings—and those who design them—can lead the energy transition. His recent paper, The Integration of Renewable Energy Systems in Green Buildings: Challenges and Opportunities, published in the International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences, has sparked widespread acclaim for its rigorous analysis, balanced perspective, and real-world utility.

This feature spotlights Gil-Ozoudeh not simply because of the academic merit of his work, but because of its policy resonance, its transnational relevance, and its capacity to shift both discourse and decision-making in two deeply interlinked regions: the United Kingdom and Nigeria.

“Green architecture is not about applying imported technology—it’s about designing intelligently within climate, culture, and constraint,” Gil-Ozoudeh says. “What works in London’s high-rises must be reinterpreted for Lagos’ low-income districts. But the underlying principles—resilience, efficiency, and accessibility—are universal.”

Buildings at the Frontlines of the Energy Crisis

Gil-Ozoudeh’s work arrives at a moment of global reckoning. According to the UK Green Building Council, over 80% of the buildings that will exist in 2050 have already been built, meaning that retrofit, rather than new construction, is where the battle for carbon reduction will be won or lost. The Future Homes Standard (due to be introduced in 2025) aims to ensure that new homes produce 75–80% less carbon emissions, but challenges remain, particularly in existing housing stock—especially in social and affordable housing sectors.

Meanwhile, Nigeria confronts a different, though no less urgent challenge. With an electricity grid that supplies only about 4,000 MW reliably for a population exceeding 220 million, most homes and offices rely on backup diesel generators, resulting in widespread air pollution, noise, and dependence on fossil fuels. The Nigeria Energy Transition Plan projects that achieving net-zero by 2060 would require at least 60% of electricity from renewables, yet current deployment remains under 20%, with solar penetration below 3% in urban households.

In both countries, buildings are ground zero for climate mitigation—and this is where Gil-Ozoudeh’s expertise shines most brightly.

“You cannot decarbonise a nation without decarbonising its buildings,” he notes. “The challenge is not merely technological. It is social, regulatory, and cultural.”

Challenging Assumptions, Designing Context

What distinguishes Gil-Ozoudeh’s contributions is the multi-scalar lens he applies. He doesn’t see renewable energy systems—solar PV, wind microturbines, geothermal, biomass—as standalone solutions. Rather, he situates them within holistic building envelopes, where passive design, thermal comfort, insulation strategies, and user behaviour all matter.

In the UK, he points out, the barriers are largely financial and regulatory. While renewable systems are technically viable and commercially available, adoption is often hindered by poor incentives, planning red tape, and fragmented responsibility between local authorities and private landlords. Smart meters, for instance, have been rolled out across the UK, but without the parallel development of intelligent building energy management systems (BEMS), their impact is limited.

In Nigeria, Gil-Ozoudeh’s analysis reveals a different pattern: the technology may be cheap, but the delivery ecosystem is weak. Inadequate installer training, poor-quality imports, and lack of maintenance culture have undermined the solar sector’s credibility. Biomass systems and biogas technologies are often ignored, despite offering viable off-grid energy pathways for rural and peri-urban communities.

“Green buildings in the Global South are not luxury,” he warns. “They are the only logical response to failing infrastructure and rising temperatures.”

Research with Reach and Results

Gil-Ozoudeh’s work is not confined to academic circles. His renewable integration frameworks—focused on local adaptability and return on investment—are now being reviewed by regional planning boards in Nigeria and circulated in professional networks across the UK. His citation footprint has surpassed 800, and his latest model for hybrid solar-biogas systems is being explored for deployment in mid-size Nigerian developments funded by diaspora co-investment groups.

In the UK, housing associations and retrofit task forces are beginning to engage with his arguments about modular renewables—suggesting that Gil-Ozoudeh’s ideas could influence future updates to PAS 2035 retrofit standards or even shape Building Regulations Part L strategies focused on energy performance.

Crucially, he has also contributed to cross-continental conversations, participating in roundtables hosted by institutions including RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects), the Green Growth Knowledge Platform, and UK-Aid-supported think tanks on energy justice. In 2024, he was invited to advice on a feasibility study exploring the transferability of UK retrofit principles to Commonwealth countries, with a special focus on urban Africa.

“We talk about technology transfer, but the real task is knowledge adaptation,” Gil-Ozoudeh remarks. “That means mutual respect, not copy-paste development.”

Grounding Policy in Practical Design

Gil-Ozoudeh’s paper lays out a detailed roadmap for what integrated renewable architecture should look like: not as a patchwork of expensive gadgets, but as a climate-responsive framework rooted in thermal dynamics, lifecycle assessment, and environmental equity. His systems-based approach accounts for variables often ignored in mainstream discourse: energy access, building orientation, urban density, community resilience, and construction materials’ embodied carbon.

One of the models he proposes—a low-rise, energy-autonomous building prototype—uses a combination of passive ventilation, rooftop solar PV, rainwater harvesting, and locally sourced compressed earth blocks. It has a carbon payback period of under six years and is cost-comparable to conventional builds once subsidies or micro-loans are applied.

Gil-Ozoudeh has called for the establishment of a “Climate-Smart Building Index” that takes into account not just kilowatt-hours saved, but also job creation, local material sourcing, and adaptive reuse of existing structures. He argues that net-zero building cannot mean zero participation by local economies.

“A building is not green unless its construction benefits local lives. That’s what sustainable design really means.”

A Global Voice for Climate-Responsive Innovation

Today, Ifechukwu Gil-Ozoudeh represents the kind of global expert the climate movement desperately needs—grounded in place, attuned to practice, but speaking across geographies. His message resonates in Glasgow and Kaduna alike: the path to decarbonised cities runs through inclusive design, distributed energy, and policy frameworks that work from the bottom up.

By spotlighting Gil-Ozoudeh’s work in this publication, we reaffirm a truth often overlooked in mainstream climate dialogue: some of the most effective and scalable ideas for building sustainability are emerging not from global capitals, but from visionary thinkers in the Global South. That the UK and Nigeria—so different in many respects—share overlapping challenges in energy equity, climate resilience, and building performance is both sobering and empowering.

In Gil-Ozoudeh’s words:

“Our buildings are either burdens or buffers. Every window, wall, and watt must now serve the planet.”

The time has come not only to listen to experts like Gil-Ozoudeh, but to act on their insights—before the walls around us become monuments to our inaction.