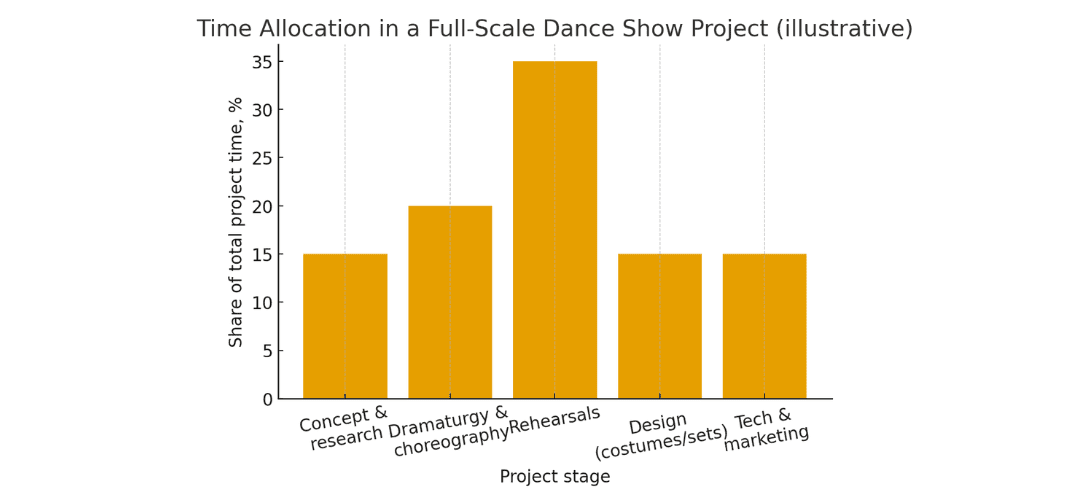

The article examines a choreographic show as a complete creative and production product rather than merely a set of dance routines. Drawing on the practice of a choreographer and artistic director with more than 15 years of experience, it analyzes the key stages of creating a performance—from the initial concept and dramaturgy to working with performers, scenography, costumes, lighting, and video content. It demonstrates that in today’s entertainment industry, a choreographer effectively performs the role of a product manager: formulating the idea, managing a cross-functional team, building a controllable process, and taking responsibility for the artistic and emotional outcome for the audience. Special attention is paid to working with socially significant themes (addiction, loneliness, traumatic experiences, historical narratives) and to the artist’s responsibility for the conceptual and emotional depth of a production.

Introduction

The mass perception of dance is often reduced to form: movements, synchronization, spectacular tricks, and visual effects. However, within the professional community it has long been evident that what truly holds the audience’s attention is not only technique, but also story, emotional journey, and meaning embedded in the performance.

Practice shows that contemporary choreographic shows in the entertainment industry and educational projects are closer to theatrical productions: they are full-scale performances with a script, dramaturgical turning points, a visual score, and a well-developed theme. With this approach, the choreographer takes on the role of a product manager—from the initial idea and research of the topic to the final premiere and audience response.

1) The Idea as the Core: From Theme to Script

The starting point of any project is the theme. In practice, these may include social topics (the fight against addiction, loneliness, violence, bullying, the search for one’s dream) as well as historical narratives (Oskar Schindler, the Siege of Leningrad, the fate of children during wartime).

Working with a theme involves several steps:

Defining the focus

It is important to narrow the theme to a specific question: not simply “war,” but, for example, the inner world of a child in a besieged city; not an abstract “dream,” but the journey of a teenager who brings a team together to achieve a goal.

Researching the material

Documentary sources, films, memoirs, and interviews are used. This helps avoid superficial or stereotypical interpretations of complex themes, especially historical and traumatic ones.

Building the dramaturgical arc

Key narrative points are defined: exposition, conflict development, climax, and resolution. At this stage, the theme is translated into the language of scenes—future choreographic episodes.

In this way, the idea becomes an internal “brief” for the entire project, guiding choreography, scenography, and costume design alike.

2) Show Structure: Scenes, Images, Rhythm

With this approach, a choreographic show is closer to a theatrical performance than to a concert number. The structure is built around a sequence of episodes, each serving a specific function.

Several principles can be highlighted:

Alternation of tension and “breathing” scenes

It is impossible to keep the audience in a single emotional register throughout. Even heavy stories require moments of hope and temporary relief so that climactic moments resonate more strongly.

A main character or group storyline

The audience must understand whom they are following—this may be a distinct character or a group moving from point A to point B.

Recurring motifs

Through movement, music, lighting, or props, motifs are introduced that return in key scenes and create a sense of cohesion.

As a result, the show becomes not a collection of unrelated numbers, but a unified work in which each scene logically follows from the previous one and prepares the next.

3) Music, Lighting, Costume, and Video as Elements of the “Product”

A full-scale choreographic show requires a unified visual and sound concept.

Music

Music is selected not only for its emotional tone, but also with dramaturgy in mind: tempo, dynamics, and transitions. Collages, documentary audio fragments, spoken inserts, and sound effects may be used.

Lighting

Lighting design emphasizes changes in location, the inner state of the characters, and the rhythm of conflict development. Work with light planes, accents, and backlighting allows the story to be “told” even with minimal props.

Costume

Costume should not be mere decoration. It defines role, era, and social status, and helps convey character development—through color, texture, and changes throughout the performance.

Video and multimedia

Video projections, graphics, and screen work add an extra dimension. In historically themed projects, this may include archival footage, maps, and documents; in social narratives, symbolic imagery that intensifies the mood.

All these elements are treated as parts of a single “product,” through which the audience receives a coherent experience rather than a set of disconnected effects.

4) Working with the Ensemble: From Teacher to Product Manager

A key feature of this approach is that the artistic director leads the project from the initial concept to the premiere, interacting with all participants in the process: children, teenagers, adult performers, studio teachers, and technical specialists.

Key tasks at this level include:

Translating complex themes into age-appropriate language

When working with children aged 5–12, themes are not presented directly. Metaphors, fairy-tale, or play-based symbolic structures are used to preserve depth without traumatizing the audience.

Creating a safe creative environment

It is essential that performers feel supported and understand the story they are part of. Emotionally heavy themes require trust within the group and a careful, sensitive approach from the teacher.

Managing the team’s resources

Long rehearsal periods, intensive staging processes, and schedule changes all require thoughtful workload planning, clear communication, and consideration of the individual capacities of participants.

In this way, the artistic director assumes the role of a product manager: not only creating choreography, but also managing the process, the team, and the overall health of the project.

5) Social Responsibility and Working with “Difficult” Themes

Narratives involving drugs, violence, loneliness, or historical trauma demand a heightened sense of responsibility from the choreographer.

Several principles are crucial:

Respect for real stories and people

When addressing biographical or historical subjects, exploiting suffering for the sake of effect is unacceptable.

A focus on dignity and hope

Even in the most challenging productions, the center of gravity shifts toward the human capacity to resist, to preserve humanity, and to find support.

Engaging with audience response

After performances, there is often a need for discussion: children’s questions, parents’ reactions, and internal group reflections. It is important not to leave the audience in a state of shock, but to help them process what they have seen.

Thus, a choreographic show becomes not only an art form, but also a tool for community dialogue around important issues.

Conclusion

Approaching a choreographic show as a production product that goes through a full cycle—from idea to premiere and subsequent reflection—fundamentally changes the role of the choreographer. They are no longer only a creator of movement, but an artistic director and product manager who:

- formulates the idea and researches the theme;

- builds the dramaturgy and structure of the performance;

- integrates music, lighting, costume, video, and scenography into a unified expressive language;

- leads the ensemble through complex emotional and technical challenges;

- assumes responsibility for the meaning ultimately received by the audience.

References

- Pavis, P. Dictionary of the Theatre: Terms, Concepts, and Analysis. University of Toronto Press.

- McLeod, K. Visual and Performing Arts in Education: Creative Approaches and Critical Perspectives. Routledge.

- Materials from international dance show festivals and championships (regulations, judging criteria, methodological recommendations of juries).

- Internal methodological materials from dance schools and choreographic ensembles working in the format of theatrical performances and show programs.