Telemedicine has changed the way people think about healthcare. A patient in Ohio can now meet a specialist in New York through a laptop screen. A therapist in California can treat a client in Texas without either of them leaving home.

What once felt futuristic is now part of everyday life. But behind every video appointment is a growing list of laws that can decide whether a company succeeds or fails.

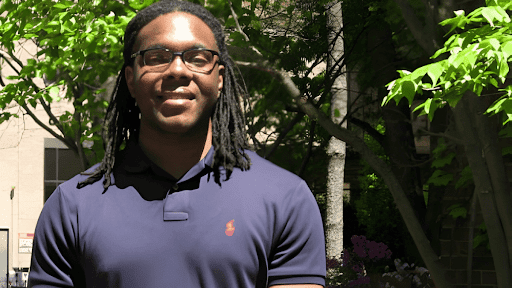

For Steven Okoye, a healthcare and corporate attorney in New York, this is the biggest challenge of modern medicine.

“The technology is moving faster than the law,” Okoye says. “Everyone wants to innovate, but no one wants to risk breaking outdated rules.”

The Problem of State Borders

One of the biggest issues in telemedicine is cross-state licensing. In the United States, medical licenses are issued by individual states. A doctor who is licensed in New York cannot legally treat a patient in Illinois unless they also hold an Illinois license.

In theory, this protects patients by keeping local oversight. In practice, it creates a maze for healthcare companies that want to offer services nationwide.

Okoye explains that this system can slow down even the most advanced platforms. “A digital health company can have the best software in the world,” he says, “but if they do not manage licensing correctly, they cannot scale.”

Some states have joined licensing compacts to make the process easier, but others have not. That leaves companies juggling dozens of renewals and different rules that can change at any time.

The Debate Over Remote Prescribing

Telemedicine also raises new questions about remote prescribing. During the pandemic, doctors were allowed to prescribe certain medications after a virtual visit. That flexibility made mental health and addiction treatment more accessible.

Now that those emergency rules are expiring, many providers are unsure what comes next.

“Doctors assume that seeing a patient on camera is enough,” Okoye says, “but the rules are different in every state. Some require in-person exams for certain drugs, while others allow telehealth follow-ups only under strict conditions.”

If a company does not follow the right steps, it can face serious penalties. Okoye encourages his clients to keep their systems simple and transparent. “If you cannot clearly explain your prescribing process, it is probably not compliant,” he says.

Privacy in a Connected World

Telemedicine does more than connect people through video. Apps now track heart rates, monitor glucose levels, and analyze sleep data. Artificial intelligence is helping doctors make faster decisions.

That kind of technology saves lives but also creates new legal concerns. Patient data moves between devices, cloud servers, and third-party vendors. Many of those systems are not covered by traditional privacy laws.

Okoye warns that this can put companies at risk. “Privacy used to mean locking up a medical chart,” he says. “Now it means protecting information across every digital tool you use.”

He advises clients to make privacy part of their design process, not an afterthought. Building secure systems from the start, he says, is the only way to stay ahead of regulators.

Building Trust in Virtual Care

Despite the complexity, Steven Okoye believes digital health can thrive if the industry focuses on one thing: trust.

“Patients need to trust that their data is safe,” he says. “Doctors need to trust that their licenses are valid everywhere they practice. Regulators need to trust that virtual care can expand access without lowering quality.”

When that trust breaks down, telemedicine becomes harder for everyone. But when it holds, the system works better than anyone imagined.

What Comes Next

The future of digital health will depend on how well technology and regulation can work together. Some states are creating flexible telehealth laws. Others are still catching up.

Steven Okoye hopes the next phase of reform will bring balance. “The goal is not to make virtual care harder,” he says. “It is to make it safer and more consistent.”

He believes collaboration between lawyers, doctors, and technology companies is the key. By sharing responsibility, they can build a system that protects patients without holding back innovation.

“The future of medicine,” Okoye says, “will be written by people who can make the law as adaptable as the technology.”