Venkatesh Gundu, Senior Manager of Data Engineering & AI Platform, explains how cloud migration, AI adoption, and cost management can drive repeatable enterprise-scale transformation.

Large enterprises have entered a decisive phase of cloud transformation. Organizations aspire to have approximately 60 % of their environment in the cloud by 2025. However, modern enterprises face a familiar paradox: they need data systems that operate faster while remaining stable, automation that enhances human judgment without replacing it, and cloud architectures that reduce costs while expanding capability.

Venkatesh Gundu sees it differently. Over sixteen years (2009 – 2025), his career has evolved in parallel with the data engineering and AI landscape, from individual contributor writing code, to technical architect designing systems, to manager shaping teams, and now to senior leader driving global transformation. Along the way, he has delivered over $5 million in cumulative cost savings, reduced infrastructure expenses by 30 to 35 %, and built AI platforms supporting more than 70 models annually, guiding distributed engineering teams that sustain operations across three continents. The methodologies and technology frameworks he developed, especially around AI-driven migration and data integration, are now referenced by other leading retailers as best practices in Data & AI modernization, helping the broader retail industry accelerate its digital transformation safely and efficiently.

That clarity has earned recognition beyond his organization. In 2025, Venkatesh Gundu received the Cases & Faces International Award in Chicago, selected from over 1,000 global applicants for innovation in enterprise data transformation. A recognized IEEE Senior Member and Hackathon Raptors Fellow, he serves as a judge and volunteer mentor at the Ohio State University Hackathon (2024), supporting the next generation of data engineers and innovators.

Moreover, he has authored four peer-reviewed publications and one white paper, sharing scalable architectures for MLOps maturity, data integration, and agentic frameworks in AI. His volunteer work with Mid-Ohio Food Bank and My Project USA reflects his belief that technology leadership demands social responsibility as well as strategic vision.

In this conversation, Venkatesh Gundu shares insights on leading large-scale transformation, adopting responsible AI, and fostering psychological safety. He deliberates on enterprise AI complexity, what legacy systems reveal about institutional memory, and why the toughest parts of cloud migration often have little to do with code.

Venkatesh Gundu, modern software infrastructure is distributed across regions, platforms, and vendors. As you’ve scaled from individual contributor to managing 20-plus engineers worldwide, how do you maintain clarity and cohesion without resorting to micromanagement?

Leadership at this scale requires a shift from directive to orchestrative thinking. When you’re coordinating engineers in the US and India to sustain 24/7 operations, micromanagement isn’t an option. Instead, you build frameworks that empower autonomous decision-making within clear boundaries.

We implemented what we call a sun model, teams distributed so that someone is always in their productive hours, maintaining continuity without burnout. But that only works if people trust the handoff protocols and understand the system architecture deeply enough to make judgment calls. My role is to define those protocols, ensure rigorous knowledge transfer, and trust the competence of the people I’ve hired. When downtime impacts Marketing, Finance, Supply Chain, Distribution Centers, Warehouse Management, and Store Operations simultaneously, you need engineers who can think, not just execute.

The hardest part isn’t technical; it’s cultural. Managing teams with diverse skill levels while supporting platforms such as Snowflake, Kafka (a platform for high-volume, real-time data streaming), and Vertex AI (Google Cloud’s AI and machine learning) requires empathy and a balance of skills. Some members are experts, others are still learning. The goal is to create an environment where asking questions is valued just as much as providing answers.

Serving thirty-five million customers across twenty-five business units means that your infrastructure decisions ripple through the entire organization. How do you balance the demand for innovation with the non-negotiable requirement for stability?

I think of it as operating in two modes simultaneously: evolutionary and revolutionary. Evolutionary changes happen continuously: performance tuning, incremental feature releases, and minor optimizations. These keep the engine running smoothly. For example, when we migrated from Teradata to Snowflake, we ran parallel systems for months. New queries went to Snowflake, but Teradata remained the source of truth until we validated performance, accuracy, and operational readiness. That deliberate redundancy costs time and money upfront, but it prevents catastrophic failures that cost far more. The migration ultimately delivered a fifty percent infrastructure cost reduction and a forty percent performance improvement because we refused to equate speed with recklessness.

The key is never confusing the two. When we migrated five hundred-plus critical business processes from SAS to Python, we didn’t flip a switch. We built a robust rinse-and-repeat methodology: convert, test in parallel, validate outputs, then cutover. That discipline allowed us to achieve one million dollars in annual savings and a twenty percent efficiency improvement without disrupting daily operations. So, innovation doesn’t require recklessness. It requires discipline.

The SAS-to-Python migration delivered clear results. What practices from that effort should organizations adopt when confronting their own legacy-system bottlenecks?

Acknowledge the emotional attachment. SAS wasn’t just software; it represented decades of institutional knowledge and career identity for some team members. If you treat migration purely as a technical exercise, you’ll face resistance. We invested heavily in training, created peer mentorship programs, and celebrated small wins publicly.

We focused on automating what truly benefited from automation. Custom tools handled most of the code conversion, but some logic still required human judgment. Chasing one hundred percent automation would have delayed the project by months, a reminder that aiming for perfection can hinder progress.

Run dual systems longer than you think necessary. We validated outputs in parallel until confidence was absolute. That patience prevented catastrophic errors and gave stakeholders proof that the new system was trustworthy. Transformation isn’t a sprint. It’s a methodical march toward a better state.

You led Teradata-to-Snowflake migrations at Big Lots. How did you align technical teams, governance standards, and business partners to replicate success across different Fortune 500 environments?

The technical migration was actually the simpler part; the harder challenge was organizational alignment. At Big Lots, we emphasized operational cost reduction.

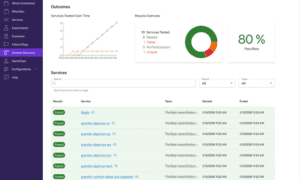

We created cross-functional steering committees that included IT, finance, and business leaders. These committees reviewed progress weekly, adjudicated trade-offs, and ensured that technical decisions reflected business priorities. Furthermore, we established clear success criteria upfront, not vague aspirations like better performance, but specific targets, such as forty percent faster query response times for category-level sales reports.

Another key was incremental delivery. We avoided attempting to migrate everything simultaneously. We prioritized high-impact, lower-risk workloads first, demonstrated value, and then used that momentum to tackle more complex migrations. As we learned, success builds credibility, and credibility unlocks resources.

High-performing engineering teams thrive on trust, not fear. In fast-moving, high-stakes environments, how do you build a culture where engineers can question assumptions, admit mistakes, and still feel valued for learning?

Blameless retrospectives are sacred. When something breaks, and it will, we ask what the system allowed, not who failed. If an engineer deployed a bug, we examine why testing didn’t catch it, why the documentation was unclear, or why the review process missed it. The goal is systemic improvement, not individual punishment.

Additionally, we invest in peer-mentorship loops. Senior engineers pair with junior colleagues not to offload tasks, but to share knowledge and hard-won experience, how to debug ambiguous issues, communicate trade-offs to non-technical stakeholders, and scope work realistically. Growth comes through observation, guided practice, and safe experimentation. Cross-training serves as another forcing function: if only one person understands a critical system, you’ve built a single point of failure. We rotate engineers across platforms and encourage curiosity over specialization. Knowledge hoarding is a cultural failure, not a personal asset.

As automation and AI reshape how enterprises operate, efficiency alone is no longer enough. What guiding principles should define this next chapter of enterprise automation to ensure progress benefits both businesses and the people behind them?

First, AI governance must be transparent. If a model denies someone a credit decision or recommends a product, the logic should be explainable. Black-box systems erode trust. Second, cost optimization is a moral issue. Enterprises that waste computing resources are externalizing environmental harm. Efficient architecture isn’t just economics; it’s stewardship. Third, inclusion requires intentionality. Homogeneous teams produce homogeneous solutions. We need engineers who ask whether something works for people unlike themselves. That’s not political correctness; it’s product quality.