The most difficult problem in modern robotics is not teaching machines how to move. It is teaching them how to learn from the real world at scale. While advances in models and algorithms continue to make headlines, the limiting factor for embodied AI is increasingly the infrastructure that determines what data robots see, how that data is collected, and whether it is trustworthy enough to shape behavior in unpredictable human environments.

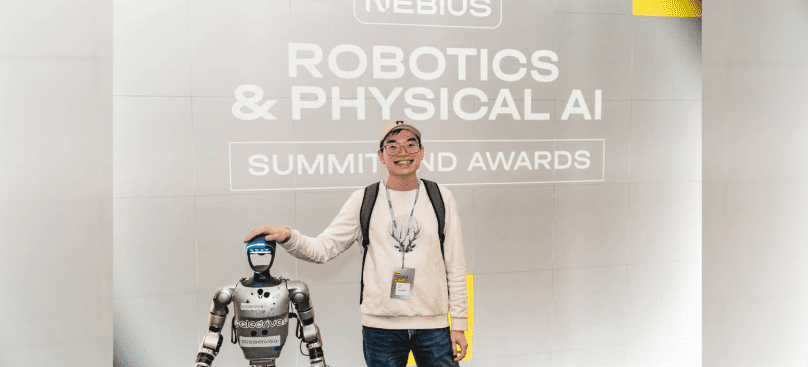

Henry Yu’s work sits squarely at this inflection point. As founding Director of Robotics Data & AI Systems at Sunday Robotics whose recent public launch out of stealth changed how the industry thinks about robotics data collection. Yu architected the data engine that underpins one of the most ambitious efforts in home robotics today. Rather than focusing on isolated demonstrations or controlled lab settings, his systems are designed to support learning across millions of real-world interactions, spanning diverse households, tasks, and physical conditions.

“Robots don’t fail because they lack good models,” Yu explains, “The greatest leaps in model robustness came from improving every layer of the data stack, from data collection hardware and software to large-scale operational processes that ensure data diversity and quality. These improvements often yield more significant gains than architectural model changes alone.”

Why Data Infrastructure, Not Model Architectures, Is the Bottleneck

Unlike large language models (LLMs) and vision language models (VLMs), which can draw from vast amounts of public text, images and videos, robotics systems rely on multimodal data that is scarce, expensive, and fundamentally difficult to collect. Training vision-language-action models requires synchronized streams of kinesthetic motion, spatial geometry, visual context, and human intent. Without a system that can orchestrate this complexity end to end, improvements to model architecture alone plateau quickly.

Yu’s work addresses this reality head-on. He designed a vertically integrated data engine that manages the full lifecycle of robotics training data, from capture and quality control to preprocessing and delivery for machine learning research. The platform supports multimodal ingestion through wearable devices, large-scale processing pipelines, and operational tooling that bridges software, hardware, and manufacturing teams.

Since its deployment, the system has enabled the production of more than 2,000 wearable data collection devices and the capture of over 10 million real-world interaction episodes, totaling more than 200 terabytes of high-quality data collected from hundreds of homes across the United States. This scale is not incidental. It is the foundation that allows robots to generalize beyond scripted tasks and operate reliably in unstructured environments.

Orchestrating Learning Across Humans, Hardware, and Cloud Systems

At its core, the data engine is not a single service but a tightly coordinated ecosystem. Yu architected six interconnected components that together form the backbone of robotics learning operations. These include identity and access management for secure, role-based access control; augmented reality applications for multimodal data capture; a unified operational hub for labeling, quality assurance, and manufacturing workflows; asynchronous processing pipelines for data intelligence and flagging; clean data delivery interfaces for machine learning teams; and over-the-air update systems for managing hardware fleets in the field.

This infrastructure allows engineers, researchers, and operators to work against a shared source of truth. Data collected in homes flows through automated quality checks, spatial validation, and preprocessing stages before it ever reaches a training run. At the same time, firmware updates, calibration changes, and device health metrics propagate back to the field without interrupting ongoing data collection.

“Learning at scale only works if the system respects reality,” Yu notes. “That means designing for failure, drift, and human variability from day one.”

From Wearable Devices to Robotic Intelligence

Yu’s contributions extend beyond software alone. He is a named inventor on multiple patents covering wearable data collection devices for training robotic systems, and time-of-flight sensors for wearable robotic training devices. These systems are designed to mirror the physical constraints of robotic counterparts, capturing fine-grained pressure, motion, proximity, and sensory data as humans perform everyday tasks. Integrated with augmented reality and spatial tracking, the wearables translate human behavior into structured training input for neural networks that control robots.

What distinguishes this work is not novelty at the device level, but how deliberately the hardware is shaped around learning objectives. The wearables are not generic sensing platforms; they are tuned to expose failure modes, edge cases, and task ambiguities that typically disappear in simulation. By constraining human motion to robotic limits and enforcing task fidelity, the system produces data that is immediately usable for policy learning rather than post-hoc interpretation.

This hardware–software co-design reflects a core theme of Yu’s work: robotics learning systems cannot be separated from the means by which data is generated. Infrastructure decisions made at the sensor, device, and orchestration layers directly determine what robots can and cannot learn, how quickly feedback loops close, and where brittleness emerges. In Yu’s systems, learning is treated as an end-to-end pipeline problem, not a modeling exercise isolated from the physical world.

Why This Work Matters for the Future of Robotics

The implications of this kind of infrastructure reach far beyond a single company. As robots move into homes, workplaces, and public spaces, their ability to learn safely and reliably becomes a societal concern. Data engines like the one Yu built define how quickly robots can adapt, how well they generalize, and how responsibly they are trained.

Crucially, improvements in data quality, diversity, and orchestration consistently outperform incremental gains from model tuning alone. By enabling long-horizon learning and zero-shot generalization through real-world data, Yu’s systems make it possible to move from narrow automation toward genuinely useful embodied intelligence.

“The models will change,” Yu says. “The data infra and pipeline define the ceiling of how good the models can be.”

Where robotics progress is often framed as an algorithmic race, Yu’s work highlights a quieter truth. The future of robotics will be built not only by smarter models, but by the invisible systems that allow machines to learn from the real world, at scale, without breaking.

His academic contributions further reinforce this systems-oriented perspective. As an author on a peer-reviewed paper presented at the IEEE and ACM International Conference on Software Engineering, Yu has contributed to advancing tooling for complex, safety-critical software systems, underscoring his broader expertise in building robust foundations for large-scale computation.