A rare conversation about metallurgy, energy systems, global supply chains, and cross-border engineering ecosystems.

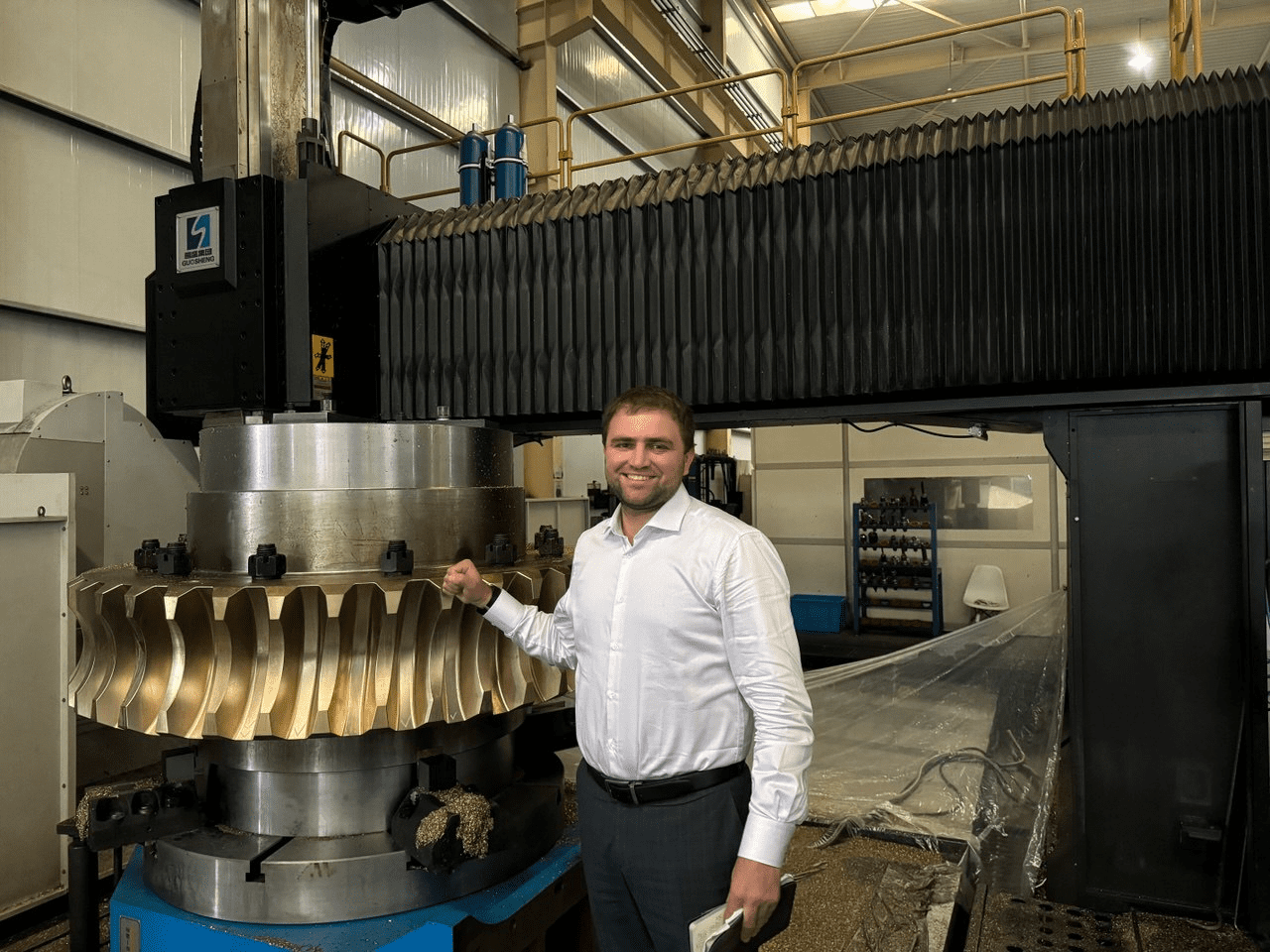

While most of the entrepreneurial spotlight in recent years has been captured by software, AI, and fintech, heavy industry is undergoing a quieter and arguably more consequential transformation. Few understand this transition as clearly as industrial entrepreneur Daniil Matyushenko, whose companies built modernization platforms for metallurgy, mining and energy enterprises across Central Asia, expanding from supply chain innovation to engineering design, and now toward an ambitious roll-out strategy connecting U.S. industrial technology to underserved markets across the former Soviet industrial corridor.

The story is not merely about manufacturing. It’s about sovereignty, export regimes, recycling loops, electrification, supply chains, and the geopolitical re-rating of industrial capabilities. TechBullion sat down with Matyushenko to discuss the modernization thesis, the China-US competitive split, and his plan to turn American industrial equipment and automation into a scalable export platform to Eurasia.

TechBullion: Daniil, let’s start with the foundational question. Heavy industry seems to be returning to strategic attention globally. Why now?

Because economies still depend on things that must be physically built and physically operated. Software can optimize processes, but it cannot smelt steel, pump ore, transmit high-voltage power, or keep industrial heat cycles stable. The world entered the last decade believing that “the physical economy was solved.” It wasn’t. It was simply outsourced and under-maintained.

COVID-19, energy shocks, sanctions warfare, and logistics disruptions showed the fragility of industrial supply chains. Now everyone is asking the same question: “Who builds the machines that keep our societies functioning?” That’s why heavy industry is back on the table.

Your career began in that physical world. Can you describe the early phase?

I entered heavy industry through supply chains, not through a CEO desk. Working in the Eurasian Resources Group (ERG), one of the region’s largest mining and metallurgy conglomerates, I was directly responsible for sourcing, validating, and commissioning equipment where the wrong part can shut down a rolling mill or smelting line worth millions per day.

This period forced me to learn not only the economics of procurement, but also the physics, metallurgy, thermodynamics, power systems, and safety regulations behind the equipment. Later, as Head of Electrical and Metallurgical Procurement, I managed multi-national supply relationships across Kazakhstan, Russia, China, Central Asia and Europe. That exposure shaped my entrepreneurial thesis: modernization was deeply under-supplied, and the region needed companies that could build rather than only import.

Eventually you founded AsiaTyazhMash, later expanding through SVM Project. What problem did these ventures solve?

At the time, most plants across the region were operating equipment designed between the 1960s and 1980s. The assets were robust, Soviet and European metallurgy was high-end for its time, but lifecycle management and modernization didn’t keep pace. Plants relied on reactive maintenance instead of planned modernization, spare parts had to be imported, supply chains were fragile, and technical documentation was outdated or fragmented.

Our approach was to build an engineering platform that could design new slag-handling systems, build 37m³ slag bowls (largest in the CIS), increase rolling mill reliability, produce spare parts with extended service life, integrate Chinese manufacturing advantages with European quality standards, and build ultrasonic heat-exchange upgrades for energy assets. In metallurgy, if you extend the life of a critical component by 20-25%, you do not just save on repairs, you avoid shutdowns that can cost tens of millions. Modernization is a form of insurance, efficiency and sovereignty in one.

Industrial sovereignty is a term we now hear more often. What does it mean in practice?

It means that if your blast furnace depends on one supplier 8,000 km away, you don’t truly control your industrial economy. The same applies to turbines, pumps, compressors, rolling mill units, industrial automation, and metallurgical spares. Modern economies discovered that you cannot claim sovereignty while outsourcing physical infrastructure. Industrial capacity is national security.

Your companies received external recognition. Can you talk about that?

We were honored to receive several awards in the industrial sector, including “Leader of Heavy Engineering” in Central Asia and the “Industry Leader Award” in Kazakhstan for metallurgy and machinery. I was also invited to serve as a jury member in innovation competitions such as Era of Innovation and Business Breakthrough, evaluating engineering, industrial automation, and export-oriented manufacturing ventures. It was a full-circle moment, from building industrial companies to helping evaluate the next generation of them.

Let’s fast-forward to your current strategy. You are now looking at the United States as an industrial expansion point. What changed?

The U.S. is entering a new industrial cycle driven by reshoring, electrification, infrastructure renewal, micro-manufacturing, and energy security. Manufacturing is returning. Recycling loops are forming. Micro-metallurgical plants are becoming viable. And there is growing attention to circular economies.

At the same time, there’s a massive opportunity connecting the U.S. to Eurasia through export corridors that are currently dominated by Chinese manufacturers. China captures the low-to-mid segment. Europe historically captured the high segment. The U.S. produces exceptional industrial equipment but under-exports it to Eurasia. I believe we can change that.

So, the thesis is not just “build in America,” but also “export from America”?

Exactly. The playbook is: build American equipment, modernize it, export it to Eurasia, and capture under-served industrial markets. This is attractive because Eurasia is not a small market. If you include Central Asia, the Caucasus, Russia, Ukraine (post-reconstruction), Belarus, Eastern Europe, and Turkey as a transit and assembly hub, you get an industrial corridor of over 300 million people. Just Kazakhstan alone had manufacturing production of $48.7 billion in 2023, with industrial output growing 7.5% in 2024. The region’s mining, metallurgy, and energy equipment needs represent a market opportunity worth tens of billions annually.

China dominates this corridor today, not because America cannot compete, but because America hasn’t been trying.

Where do you see the U.S. advantage?

In five critical areas. First, the production of modern, high-quality, high-efficiency equipment itself. American manufacturing standards, materials science, and engineering precision create equipment that simply lasts longer and performs better under demanding industrial conditions. Second, documentation and certification, where American companies excel at providing complete technical specifications, compliance documentation, and regulatory certifications. Third, lifecycle management and safety, including planned maintenance protocols, spare parts availability, and operational safety systems. Fourth, industrial software and controls, where the U.S. leads in automation, monitoring, and process optimization technologies. And fifth, energy and emissions efficiency, which is becoming critical as plants face pressure to reduce their environmental footprint.

Chinese suppliers win on price and speed. Americans win on quality, compliance, reliability, and interoperability with digital systems. Eurasian plants are now under pressure to meet global standards, reduce energy intensity, and extend equipment lifespans. This is precisely where American equipment can gain significant market share.

Let’s talk about your micro-metallurgy project. What exactly are you building?

One of my primary U.S. projects is building a grinding ball production facility using recycled railroad rails as feedstock. Grinding balls are steel spheres used in ball mills for crushing ore in mining operations, cement plants, and power stations. The global grinding media balls market is valued at approximately $8 billion and growing at 5% annually, with North America representing over $1 billion of that market.

What makes this interesting is the circular economy aspect. We take decommissioned railroad rails, which are high-quality steel, and process them into grinding balls through an energy-efficient rolling process rather than traditional melting and casting. This cuts energy consumption by up to 40% compared to conventional production methods and dramatically reduces emissions.

Why is there demand for this product in the U.S.?

The U.S. currently imports significant volumes of grinding balls, primarily from China and Turkey. Domestic production is limited. Meanwhile, the mining industry, cement manufacturers, and coal power plants need constant supplies, these balls wear out and need replacement every few months depending on the application. There’s chronic demand, and it’s all long-cycle business.

The first phase of the project creates 35-38 high-skilled manufacturing jobs, supports American mining and energy industries, reduces import dependence, and demonstrates how micro-metallurgy can work at scale. We’re looking at states with strong mining or industrial presence for the first facility, with plans to replicate the model regionally to stay close to customers.

How does this connect to your Eurasian export strategy?

After we establish domestic production and prove the business model, the same grinding balls can be exported to Eurasian mining clusters where Chinese suppliers currently dominate. American-made grinding balls with superior documentation, quality control, and metallurgical consistency can command premium pricing in markets that are upgrading their operations. It becomes a two-way value proposition: serve U.S. industrial needs while building an export platform.

We’re also exploring aluminum recycling using the same infrastructure. High-quality aluminum scrap from food packaging and electrical sources can be processed locally rather than exported as waste. Recycling aluminum uses 95% less energy than primary production and cuts greenhouse gas emissions by 97%. This fits perfectly into the circular economy model.

Let’s break down your export strategy. How do you intend to bridge the markets?

Our export model is hybrid, combining OEM partnerships with independent integrator capabilities. But there’s a crucial element that many people underestimate: the Eurasian market has its own specific dynamics. Selling and promoting capital equipment, especially production machinery and industrial systems, requires specialists who thoroughly understand the market specifics and personally know the major players. Foreign specialists trying to enter this market from scratch face nearly impossible barriers. You need someone who speaks the language, understands the procurement culture, knows the decision-makers personally, and can navigate the technical, financial, and political nuances.

This is where my background becomes strategic. I’ve spent years building relationships across Kazakhstan, Russia, Central Asia, Ukraine, and Belarus. I know the plant managers, the procurement heads, the engineering directors. I understand how decisions are made, what documentation is required, how payment terms are structured, and what technical adaptations are necessary for local conditions.

We see three layers in our model. First, we collaborate with American OEMs in metallurgical equipment, rolling mill spares, pumps and compressors, industrial hydraulics, heat-exchange, and industrial automation. OEMs gain access to export markets they are not currently reaching, because we provide the local market expertise they lack.

Second, U.S. equipment is then adapted, serialized, modernized, documented, certified, and bundled with controls for the Eurasian environment, where infrastructure, power grids, and standards differ. Third, we provide installation, commissioning, warranty, lifecycle parts, maintenance, training, local compliance, and after-market spares. This closes the loop and makes American equipment competitive against Chinese suppliers who usually limit service to the initial installation.

Who dominates these Eurasian markets today?

Primarily China and partially Turkey. China built full supply chains for industrial hardware, automation, castings, forgings, and rolling components tailored for Eurasia. Europe partially withdrew due to political risk. The U.S. didn’t enter the segment strategically. This creates a window. If the U.S. enters now with integrated equipment plus automation plus lifecycle support, segments of the market can be retaken.

You mentioned earlier that there are serious engineering challenges in the region. Can you elaborate?

One of the biggest problems in CIS countries today is the shortage of qualified designers and engineers who can properly specify heavy equipment parameters. The engineering knowledge base is eroding. Many senior specialists are retiring, and the younger generation often lacks the deep technical training in metallurgy, thermodynamics, and materials science that complex industrial systems require.

There’s also a historical irony here. Much of the heavy industrial infrastructure across the former Soviet Union was actually built with significant help from American specialists, engineers, and designers in the early-to-mid 20th century. American expertise shaped many of the foundational metallurgical and mining operations. Now we’re seeing a potential return of that relationship, but in a completely different context.

What role does automation and software play in all of this?

A major role, and this is where the transformation becomes truly dramatic. The U.S. has enormous advantage in PLCs, SCADA, sensors, defect monitoring, predictive maintenance, and digital twins. But it goes further than that now. Modern equipment needs to be smart. We’re moving toward AI-driven process optimization, real-time quality monitoring, predictive maintenance that can prevent failures before they happen, and integrated control systems that can adjust parameters automatically based on thousands of data points.

Eurasian plants still operate largely on analog or semi-digital systems. Equipment that was state-of-the-art in the 1970s or 1980s had minimal instrumentation. Today’s industrial environment demands completely different capabilities. You need smart sensors, automated controls, machine learning algorithms that optimize energy consumption, reduce accident rates, improve process quality, and increase productivity while ensuring final product consistency.

This creates a massive retrofit and modernization market. Companies like Rockwell, Emerson, ABB US, Eaton, and Honeywell have technologies that can transform these operations. The equipment needs to be outfitted with modern intelligent measuring and control devices. That’s not just an upgrade, it’s a fundamental transformation of how industrial processes operate. And this is precisely where American technology excels and where the export opportunity is most compelling. Automation and AI integration is how U.S. can win the mid-to-high tier.

Let’s close with a broader vision. What do you see as the next industrial cycle?

If the 20th century industrial cycles were mechanization, electrification, and automation, then the 21st century will be about integration. Integration of physical infrastructure with digital controls, metallurgy with electrification, manufacturing with recycling loops, procurement with finance, energy systems with emissions, and workforce with automation. Countries that master integration will define the next century. Industrial strength is returning as a measure of geopolitical relevance. We are simply positioning ourselves to build part of that infrastructure.

Daniil Matyushenko is an industrial entrepreneur focused on heavy machinery, engineering, metallurgical modernization and industrial supply chain transformation across Eurasia. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Physics, a Master’s in Economics, and an MBA from Moscow State University. He served in senior procurement and engineering roles at the Eurasian Resources Group (ERG), founded AsiaTyazhMash and SVM Project, received the Leader of Heavy Engineering and Industry Leader awards in Central Asia, and served as a jury member at Era of Innovation and Business Breakthrough. He is currently developing a hybrid OEM plus integrator platform to connect U.S. industrial equipment and automation to Eurasian export markets, with initial projects focused on micro-metallurgy and circular economy manufacturing in the United States.