Driving at night has become a source of anxiety for many motorists. While modern vehicles are equipped with headlights that are brighter than ever, this technological leap has brought a controversial side effect: blinding glare. The complaint is universal—drivers feel assaulted by the intense blue-white light of oncoming traffic, often causing momentary blindness.

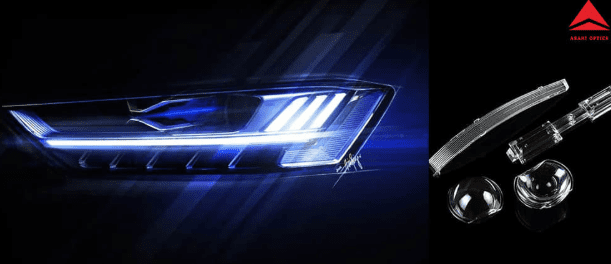

For automotive engineers and lighting designers, this presents a complex paradox. The market demands higher lumen output for better visibility, but safety regulations and driver comfort demand strict control. The solution to this crisis does not lie in dimming the light source, but in rethinking how we shape it. This is where the engineering precision of secondary optics becomes the most critical safety feature on a vehicle.

The Physics of the Problem

To understand why glare occurs, we must look at the light source itself. Traditional halogen bulbs emitted light omnidirectionally, which was easily captured by a simple reflector cup. LEDs, however, are directional point sources with high intensity. When an LED headlight is designed poorly—often by simply placing a powerful chip behind a cheap, magnifying piece of plastic—the result is uncontrolled scatter.

This scattered light, or “stray light,” projects upwards above the horizon line. For the driver behind the wheel, the road looks bright. But for the oncoming driver, that stray light hits directly at eye level. This is why the industry is rapidly shifting away from simple reflectors toward sophisticated projector systems that use highly engineered lenses to manage every photon.

The Critical Role of the Cut-Off Line

The holy grail of low-beam headlight design is the “cut-off line.” This is the sharp boundary between the bright illumination on the road and the darkness above it. A razor-sharp cut-off allows a manufacturer to push the intensity of the light further down the road (increasing the range) without projecting any light into the eyes of oncoming traffic.

Achieving this requires automotive lighting lenses that are manufactured with micron-level tolerance. Unlike general illumination, automotive optics must handle complex geometries. The lens must spread light widely to illuminate the roadside (for pedestrians and signs) while simultaneously focusing a “hot spot” in the distance for highway driving, all while maintaining that strict dark zone above the horizon.

If the surface of the optical lens deviates even slightly during the molding process, the cut-off line becomes blurry. This blur leads to leakage—light that drifts upwards into the glare zone. Therefore, the capability to design and mold these lenses is a specialized skill set that separates top-tier suppliers from generic molders.

Thermal Management and Material Science

Another invisible challenge in automotive lighting is heat. While LEDs run cooler than halogens, the electronics and the compact nature of modern headlight clusters generate significant localized heat. Furthermore, the lens is the barrier between the delicate electronics and the outside world, facing constant UV radiation from the sun and impact from road debris.

This environment is brutal for optical materials. We often see older cars with yellow, cloudy headlights. This is a failure of material science—usually, a polycarbonate (PC) lens that has degraded due to UV exposure or heat stress.

For a reliable automotive optical system, engineers must choose materials that balance high transmission rates with extreme durability. This often involves using optical-grade Polycarbonate with specialized coatings or additives. The design phase must also account for thermal expansion; if a lens expands too much when the headlights heat up, it can shift the focal point, ruining the beam pattern designed so carefully in the software.

The Rise of Matrix and Adaptive Driving Beams (ADB)

The industry is not stopping at static low beams. The future lies in Adaptive Driving Beam (ADB) technology and Matrix LEDs. These systems use cameras to detect oncoming vehicles and automatically shut off specific segments of the LED array to create a “shadow tunnel” around the other car.

This technology allows a driver to drive with high beams constantly on, maximizing visibility without ever blinding others. However, the optical complexity here creates a massive challenge. The lenses for Matrix systems often involve complex multi-lens arrays or silicone micro-optics.

Sourcing these components requires a supply chain partner capable of handling a diverse range of optical products. Manufacturers need suppliers who can transition from producing massive, thick-walled outer lenses to tiny, precise collimators for individual LED chips within a matrix system. The ability to iterate designs quickly—from prototype to mass production—is essential as car models update faster than ever before.

Conclusion

As we move towards autonomous driving and smarter vehicles, lighting is evolving from a basic functional requirement into a sophisticated communication tool. Yet, the fundamental principle remains unchanged: uncontrolled light is dangerous.

The “glare crisis” on our roads is not an inevitable consequence of LED technology. It is a consequence of cutting corners in optical design. By prioritizing high-precision lenses and working with manufacturers who understand the intricate balance of physics, materials, and regulation, the automotive industry can finally deliver on the promise of LEDs: brighter roads and safer drivers, without the blinding side effects.