Talk to any character artist long enough and the same story comes up. You sit down to draw, open a stack of reference images, maybe take another quick selfie with bad lighting, and still can’t get the pose to behave. The idea in your head is sharp; what lands on the canvas is stiff or slightly off.

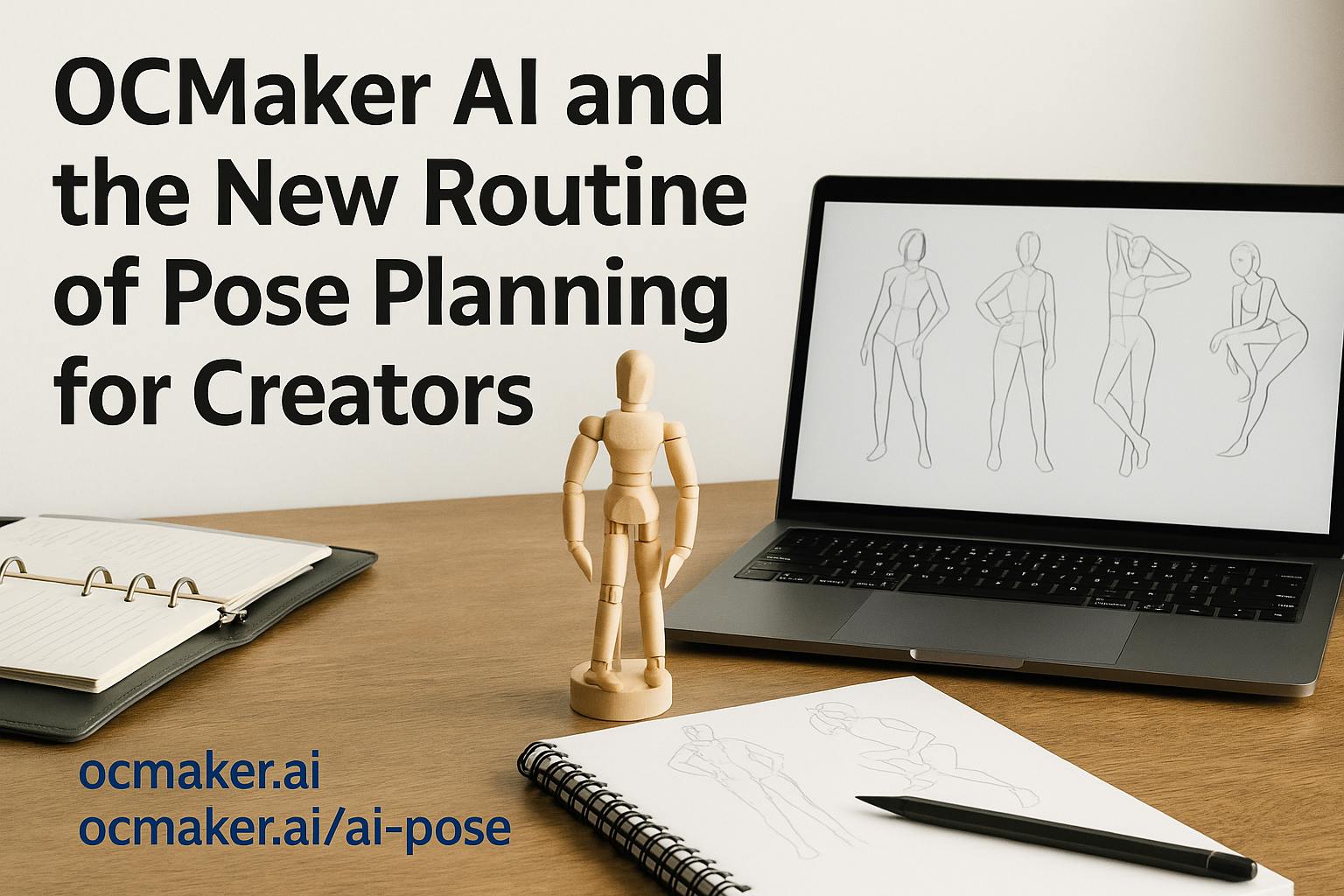

Over the last couple of years, tools built specifically for that problem have started to show up in everyday workflows. One of the names that keeps getting passed around in artist discords and small studios is OCMaker AI. Paired with its browser-based free AI pose generator, it gives illustrators, VTubers, webtoon teams, and solo game devs a fairly simple promise: lock in a pose once, keep reusing it when the character shows up again.

The idea sounds small, but it changes how people plan drawings and even how they brief each other inside a team.

Why posing becomes tricky once a character “sticks”

Designing a new OC is fun the first few times. You try different outfits, haircuts, colours, maybe a weapon or two. After that, a different challenge appears: making the character feel like the same person every time they appear in a thumbnail, a poster, or a panel.

Pose is a big part of that. A slightly hunched back, hands always in pockets, a way of leaning on a sword or coffee bar – those little habits become recognisable. When the posture changes randomly from illustration to illustration, the illusion cracks. People may not be able to explain what is wrong, but they feel the inconsistency.

Maintaining that sense of sameness is hard when each drawing starts from a different reference photo or a quick guess. Artists who publish regularly feel it the most: weekly webtoon episodes, streaming overlays, new banners every time there’s a collab. Anything that can stabilise pose across all those outputs is worth a serious look.

From “grab whatever reference you can” to a pose plan

Most of us were taught roughly the same way: collect reference, build a mental library, practice gesture drawing. That still matters. What has changed is the amount of content a single creator is expected to produce, especially if they also run social channels or a small brand.

One way to look at it is to compare a traditional reference habit with a more deliberate pose workflow:

| What you’re doing that day | Old habit | Pose-first habit |

| First pass on a new illustration | Dig through screenshots and photos | Spin up a few quick pose options for that exact scene |

| Bringing back a recurring character | Try to remember last week’s angle | Pull the saved pose for that character and adjust |

| Preparing promo graphics | Redraw similar stances from scratch | Recycle one or two “hero poses” across all materials |

| Handling a late change of brief | Redo composition around a new pose | Swap in another stored pose with similar framing |

Nothing in that table replaces drawing skill. It just acknowledges the reality that reference is now something you need to manage, not only collect.

The role OCMaker AI plays in this process

In practical terms, OCMaker’s tools sit somewhere between a pose sketchbook and a light production system.

- For webtoon and manga teams

A series often revolves around a small cast. Each character can be given a short “pose pack”: a neutral standing shot, a seated version, one or two dramatic angles, and a couple of emotional close-ups. Once those are settled, artists reuse them as a base when new scenes are planned.

- For VTubers and streamers

Models might be 2D or 3D, but the static graphics around them – schedules, panels, shorts thumbnails – still need illustration work. Keeping posture consistent across all of that helps viewers recognise the channel instantly when it scrolls past.

- For small studios and solo game devs

Concept artists, marketing designers, and UI artists often share the same characters. When a central pose library exists, everyone is less likely to invent their own version of the hero from memory.

Because the generator runs in the browser, it usually ends up as a normal tab next to the drawing app, reference board, and project tracker rather than a separate “special” tool.

Simple habits that make pose tools work better for you

The teams that get the most out of pose generators tend to treat them as a planning step rather than a magic button. A few patterns show up again and again:

- Start rough, refine later.

The first pose pass doesn’t need perfect anatomy or costume details. It just needs to capture weight, tilt, and overall attitude. Cleanup and style happen in the drawing software.

- Limit the number of standard poses.

For a main character, five to ten core poses are usually enough: relaxed standing, talking, arguing, sitting at a desk, action shot, and maybe one “poster” angle. Too many, and nobody remembers which ones are actually canon.

- Name poses by situation, not just number.

Labels like “rooftop-lean,” “tired-desk,” or “victory-jump” are easier to recall during a deadline than “Pose_07”.

- Test them at small sizes.

Many viewers first encounter a character on a small phone screen. If the pose still reads clearly in a tiny thumbnail, it will probably work on print and big screens as well.

These small organisational choices sound mundane, but they remove a lot of friction when a project reaches its tenth or twentieth asset.

Beyond the canvas: branding and business

TechBullion readers tend to care not only about drawing but also about what sits around it: channel growth, product launches, sponsorships, and platform changes. Pose consistency leaks into all of that.

- Marketing teams can reuse art more confidently when the character feels stable.

- Licensing and merch become easier because key art looks related, not like a random collage.

- Crossovers with other creators are smoother when you can provide a simple pose sheet instead of a vague description.

In other words, a pose library is not just a creative convenience; it is a small piece of infrastructure that supports everything built on top of the character.

Final thoughts

For a long time, pose planning lived in private notebooks and half-finished sketch files. Artists knew which angles worked for their characters but had no straightforward way to organise and share them. As content cycles speed up and characters need to appear across more formats, that old, improvised approach starts to creak.

Tools like OCMaker AI do not replace drawing practice or individual style, and they are not meant to. What they offer is a more deliberate way to handle one stubborn part of the process: deciding how a character stands, sits, and moves from one appearance to the next. Once that is under control, the rest of the work – expression, lighting, costume, story – has a much stronger base to stand on.